Review by

Eric Hillis

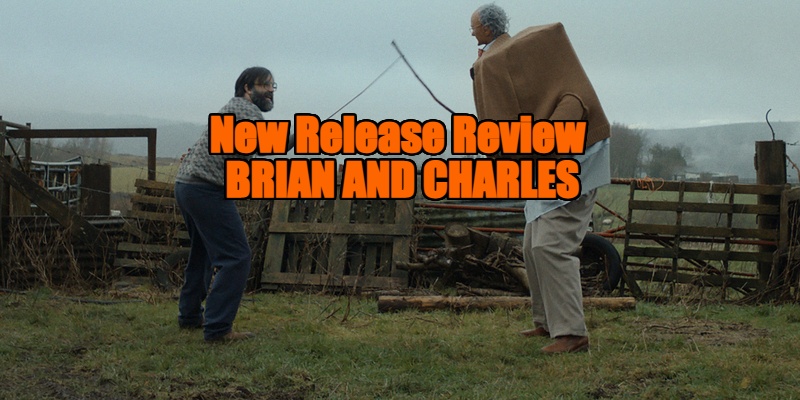

Directed by: Jim Archer

Starring: David Earl, Chris Hayward, Louise

Brealey, James Michie, Nina Sosanya

British comedian David Earl is best known for his appearances in

various Ricky Gervais projects, most recently the Netflix series

After Life. The influence of Gervais can be found in Brian and Charles, Earl's first foray into the world of feature filmmaking, co-written

with fellow comic Chris Hayward and directed by

Jim Archer. Like The Office, it adopts a Spinal Tap-esque mockumentary approach, its protagonist seemingly followed

everywhere by an unseen camera crew.

The technique is employed here in a manner that doesn't seem to have

been very well thought out. If you've ever watched a found footage

horror movie and found yourself asking why anyone would still be filming

under such circumstances, you'll likely ask similar questions at various

points in Brian and Charles. When we meet Brian (Earl), a lonely, socially awkward eccentric

inventor who lives in rural Wales, we wonder if there really is a camera

crew or if he's simply speaking to himself. But early on an unseen

director has a verbal interaction with Brian, which cements the film's

mockumentary approach. It's largely forgotten about from that point,

with sequences that feature so many camera angles the documentary crew

would need to be larger than that of a Michael Bay movie to capture the

footage. Also, nobody but Brian ever acknowledges the presence of the

cameras. The approach comes off as little more than a crude way to

establish the character of Brian by having him give us a guided tour of

his lonely world in the film's opening scenes. From then it becomes

something of an inconvenience that the movie hopes we forget

about.

If you can forget about it, Brian and Charles is a minor

delight. Earl and Hayward have crafted a Frankenstein tale by way of

'80s movies like Short Circuit, one with bags of charm. Stumbling across a mannequin head while

combing a trash heap for inspiration, Brian decides he's going to build

himself a robot. The result is Charles, a hulking android with a washing

machine for a chest and a glowing blue eye. If you grew up watching

British kids' TV in the '80s, you'll note the resemblance to the popular

ventriloquist's dummy Lord Charles, no doubt an inspiration for Earl and

Hayward (the latter performs inside the bulky robot suit).

Despite spending "72 hours" working on his creation, Charles refuses to

come to life for Brian. That is until there's a lightning storm, and

Brian finds himself suddenly sharing his home with a seven foot tall

companion. Much of the comedy comes from the developing relationship

between the titular duo. It all starts off well with the two becoming

fast friends, but Charles' mental evolution means he reaches the android

equivalent of his teen years after a few days. This of course means he

starts to rebel against his creator, spending time in his room blasting

music in a huff over Brian's refusal to allow him to travel to Honolulu,

a destination he becomes obsessed with after watching a TV travel

show.

A subplot about a family of local wrong 'uns getting their hands on

Charles is brought to the forefront for some final act drama, as is a

narrative concerning Brian's relationship with an equally shy woman (Louise Brealey). But the movie is most successful in its middle section when we just

get to hang out with Brian and Charles as human and robot develop a

bond. Despite being confined to a suit that doesn't allow for much

expression, Hayward displays an understanding of how to mine laughs from

a character that can't emote. The way he moves his head and leans in

awkwardly during conversations provokes laughs for a reason I can't

quite get to the heart of – some things are just funny.

Brian describes his creation as ending up with a blancmange when he was

aiming for a sponge cake, but he claims to also enjoy blancmange. That's

a fitting allegory for Brian and Charles. With a bit more polish it may have been a more satisfying sponge

cake, but blancmange is good enough in this case.