Review by

John Bennett

Directed by: Eliza Hittman

Starring: Harris Dickinson, Madeline Weinstein, Kate Hodge,

Neal Huff

In 1953, Ray Ashley, Ruth Orkin and Morris Engel released

Little Fugitive, a film made completely independently of Hollywood hegemony. The film

followed a young boy as he explored Coney Island after running away from

home, finely capturing the unique flavor of South Brooklyn. In representing

the special atmosphere of the southern tip of the New York borough as seen

through the eyes of a youth, Eliza Hittman gives us the 21st

century's correlative to Little Fugitive with

Beach Rats, her second feature after 2013's It Felt Like Love. With Beach Rats, Hittman manages to quietly weave themes of addiction, peer pressure,

poverty, family strife, locale and - most importantly - sexuality into one

deeply engaging indie film.

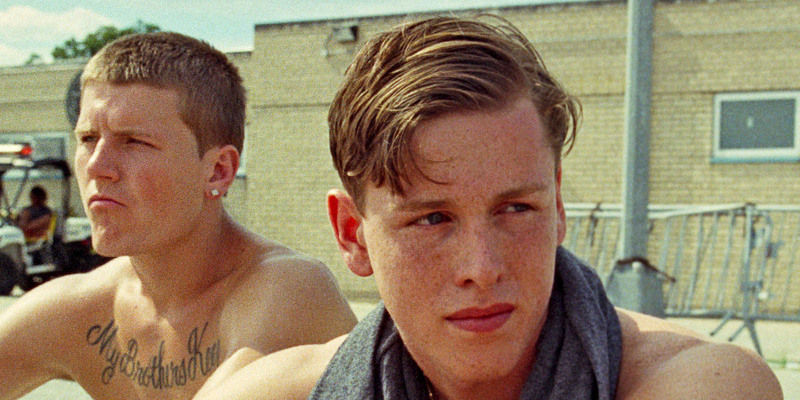

Beach Rats revolves around Frankie (played by

Harris Dickinson, who gives a striking performance in his feature

film debut), a teenager who leads an idle existence. On summer nights, he

hangs out with his ne'er-do-well friends as they drink, pick pockets, pop

pills, and scrounge for weed all over South Brooklyn, whose night sky is

often illuminated by the neon colours of beach fireworks or the flashing

lights of nightclubs. At home, Frankie’s father is slowly dying of cancer,

and the teen maintains somewhat contentious relationships with his tired

working mother (Kate Hodge) and his precocious younger sister (Nicole Flyus). When away from friends and family in the privacy of his room, Frankie

cruises adult chatrooms, slipping out of the house to have sexual encounters

with older men. In addition to these encounters, he also explores his

sexuality with Simone (Madeline Weinstein), a girl his age with whom

he seems to be testing the waters of a heterosexual romance.

Hittman, who both wrote and directed the film, adroitly crafts

Beach Rats as a film of tones and atmosphere, forgoing a

plot-driven structure that wouldn't have served the material nearly as well.

Frankie's father's illness is never over-explained. Instead, the viewer gets

one or two fleeting glimpses of the dying man, whose spectral presence

subtly underscores the family's general financial and health problems.

Similarly, Hittman presents Frankie's addiction to opioids in a naturalistic

way that eschews the potential dramatic histrionics of overdose or

withdrawal. The same goes for the petty criminal activities that Frankie and

his friends aimlessly commit. In one sequence that brings to mind the best

moments of Bresson's Pickpocket (1959), one friend quietly

steals a wallet from an unsuspecting man waiting in front of the friends in

line for a ride. They pass the wallet down the line to Frankie, who empties

it of all its cash, before they pass it back up the line and sneak it back

into the man's pocket. Again, there is no dramatic confrontation - just a

small moment that evokes the petty criminality that hangs around the friends

like a cloud of dust. These moments, all realistically suggestive rather

than expository, finely represent this unique milieu, whether under the

coloured lights of nightclubs and vape lounges, in the blazing summer sun,

or in the sad darkness of empty streets and rooms.

If Beach Rats is full of quiet moments, then it's the film's

sex scenes that constitute the brunt of the film's dramatic action. In its

depiction of a youth embarking on risky self-directed sexual adventures,

Beach Rats strongly resembles François Ozon's

Young & Beautiful (2013), in which a beautiful adolescent

(Marine Vacth) decides, for no apparent reason, to work as a prostitute.

Vacth and Dickinson bare a strong physical resemblance to one another, a

similarity that speaks to the androgynous magnetism both actors exhibit on

screen. Yet where Ozon is at times overly trenchant with his heroine's

sexual activity (even if Vacth plays the character with Deneuve-level

detachment), Hittmann steps back, allowing us to witness Frankie's sexual

experiences in a very factual way without forcing us to view these moments

through lenses of judgement, fetishisation, or any other kind of

meta-commentary. As a result, these sequences, whose graphic contents

objectively create a certain amount of unease in the viewer, slowly and

naturally build to an ending that's both tragic and ambiguous; Frankie's

unsure attempts to communicate the complex facets of his sexuality to both

his friends and a date leads inexorably to a moment of violence. Yet even

during this climactic moment, Hittman manages to keep a distance as she

succinctly merges her film's themes into one simple moment of confused

anguish for the film's hero. Through her objective sense of distance,

Hittman allows Frankie's sexuality to become the catalyst for a quiet, human

tragedy.

In general, Hittman thoughtfully blends the work of her collaborators.

Dickinson's probing gazes suggest a rich and confused interiority that gives

Beach Rats much of its narrative drive.

Nicholas Leone's unobtrusive score has a similar sad lilt as Jean

Constantin's music for Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959).

Cinematographer Hélène Louvart expertly teases out the neon colours

of beach fireworks and boardwalk amusements, while also showing as a visual

counterpoint just how dark cities and beaches can be at night as the titular

beach rats nefariously and listlessly wander between dunes and in and out of

small, old city houses.

If Beach Rats is flawed, it's flawed in a good way: it feels

slightly incomplete. Frankie is such a compelling character in the middle of

such a compelling urban environment that we're left wanting more by the time

the credits roll. But this is a good problem for a film to have; it speaks

to the sad, dangerous fascination that Beach Rats is

consistently able to generate.

Beach Rats is on MUBI UK now.