Review by Eric Hillis

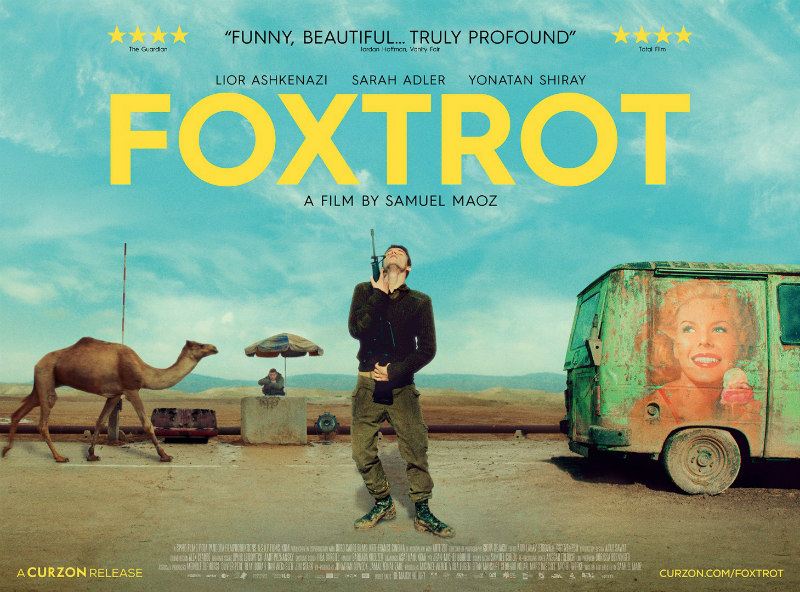

Directed by: Samuel Maoz

Starring: Lior Ashkenazi, Sarah Adler, Yonaton Shiray, Shira Haas

For as long as I've been alive, barely a day has passed in which Israel hasn't featured in the news in some capacity. For a small Middle Eastern country it sure punches above its weight when it comes to ruffling the world's feathers. Saying the wrong thing about Israel can cost you a career in politics, as US and UK politicians have recently discovered. Criticism of Israel's occupation of Palestine can see you branded an anti-semite by both conservatives and liberals, which of course is as nonsensical as being accused of bigotry against Catholics for criticising the crimes of the Vatican. Some of the most outspoken opponents of Israeli policy are themselves Jewish, and Israel is itself home to an outspoken liberal class who oppose their own government, just as every other American hates Trump and half of Brits wish to remain in the EU.

In recent years Israeli filmmakers have increasingly used their medium to comment on a society they're uncomfortable existing within. A case in point is director Samuel Maoz, whose 2009 drama Lebanon drew the ire of Israeli hardliners for its no-holds-barred depiction of the 1982 Lebanon War, a conflict Maoz served in as a young solider.

That it's taken a decade for Maoz to produce a followup, despite the accolades Lebanon received, tells you how controversial his views are seen as. His latest, Foxtrot, bluntly uses the titular dance - where the dancer always ends up back at the point they began - as a blunt metaphor for the seemingly endless situation his country is mired in.

His film too has the structure of a foxtrot, opening and closing with two extended bookends that ironically echo each other. These portions concern wealthy couple Michael (Lior Ashkenazi) and Dafna (Sarah Adler) Feldmann, who receive the news that their young son Jonathan (Yonathan Shiray) has been killed while manning a checkpoint in a remote part of the country.

The middle portion of Maoz's film takes us back in time to said checkpoint, where Jonathan and three other young men live in a tin shack that is slowly sinking into the mud beneath them. Most of their work involves raising the guard rail to allow a camel to pass through, but occasionally they have to stop motorists and check out their paperwork.

The bookends focussed on Jonathan's parents play out in a sombre, self-serious manner that comes across as false, not helped by Maoz's lazy use of Arvo Part's 'Spiegel im Spiegel', the most overused piece of music in all of cinema, and distracting camera angles to portray an unearned melancholia. Michael and Dafna simply aren't very interesting, and the former is rendered downright contemptible given his cruel treatment of the family dog. Maoz fails to sell their grief, or lack thereof, in any tangible way.

It's the middle act of Foxtrot where Maoz gets to play to his strengths, delivering what amounts to a short anti-war film, one which taken out of the context of the rest of Foxtrot, might be the best of its kind since Brian de Palma's Casualties of War. Kubrick is clearly an influence on Maoz, with echoes of Paths of Glory and Full Metal Jacket to be found here, and with its focus on young men going quietly mad in a tin can, it has much in common with John Carpenter's sci-fi comedy Dark Star.

Some of the images Maoz and cinematographer Giora Bejach conjure up here rival Apocalypse Now in finding a grim beauty in a militarised landscape, and the final tragic sequence of the portion is as suspenseful as the work of any of Hitchcock's students. Sadly this middle section only constitutes half of the running time of Foxtrot, but it more than makes up for the unconvincing grief-driven segments it's bracketed by. Maoz's talents suggest he might be working in Hollywood were that town not so tied to the interests of his home country's government.

Foxtrot is in UK/ROI cinemas March 1st.