Cult filmmaker Larry Cohen sadly left us on March 23rd.

Words by Eric Hillis

The New American Cinema movement of the '70s can be broken down into numerous cliques - the Movie Brats (Spielberg, De Palma, Coppola, Schrader et al), the Anti-Establishment Auteurs (Ashby, Altman, Rafelson and co.), the Corman crew (Demme, Bartel, Kaplan etc) and so on - but Larry Cohen, who came into his own during the '70s, can't be lumped in with any other filmmakers. His was a unique, singular vision. As a director, writer and producer, Cohen was a filmmaking movement all of his own.

Cohen was born in New York in 1941, and like so many filmmakers of his generation, his love of the movies developed from a childhood spent soaking up films in the many cinemas the Big Apple had to offer. While still in his teens, Cohen began working in TV, becoming a prolific writer, penning episodes of numerous hit shows. He's responsible for one of the best episodes of The Fugitive - 'Scapegoat', in which David Janssen's Richard Kimble risks his neck by returning to a town he had previously fled in order to clear an innocent man of his own murder. As Cohen's reputation in TV grew, he began creating his own shows - western Branded, wartime drama Blue Light, sci-fi-thriller The Invaders and Coronet Blue, a Bourne Identity-esque espionage series about an amnesiac whose only memory is the show's title.

After penning a few theatrical and made for TV movies, Cohen grew frustrated at seeing his scripts mangled. He decided to become a director primarily to protect himself as a writer, and became a producer to protect himself as a director. He made his directorial debut in 1972 with Bone, a controversial race satire starring Yaphet Kotto as an African-American home invader who discovers the white couple he's taken hostage are even nastier than himself. Touching on subject matter no filmmaker would touch today, Bone found an audience with African-American cinemagoers, which would lead Cohen to dabble in the Blaxploitation genre, teaming up with star Fred Williamson for Black Caesar and its sequel Hell Up in Harlem. This would see Cohen return to his native New York, shooting on the city's then edgy streets, usually without a permit. When Harlem's mobsters attempted to extort the production of Black Caesar, Cohen instead offered them parts in the movie, a trick he would repeat two decades later with the gangsters of Gary, Indiana for 1996's Original Gangstas. It's said that crime in Gary was almost nonexistent during the period Cohen was shooting his film there, so preoccupied were the city's rival gangs.

The breakup of the Hollywood studio system saw a lot of talented film technicians left without work, replaced by bearded kids straight out of film school. Cohen used this to his advantage, employing aging crew members who had worked on some of Hollywood's greatest movies. For his first entry in the horror genre, 1974's It's Alive, Cohen landed composer Bernard Herrmann, who had found himself struggling for work following a falling out with his primary collaborator, Alfred Hitchcock. Herrmann's darkly lush score adds a wealth of production value to what is essentially a b-movie, and the revitalised Herrmann would go on to work with Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver) and Brian de Palma (Obsession) before his death in 1975. Cohen was one of the last people to speak with Herrmann, having met for dinner to discuss collaborating once again on 1976's God Told Me To mere hours before Herrmann would suffer a heart attack in his hotel room. Herrmann had burned so many personal bridges during his life that it was left to Cohen to organise his funeral.

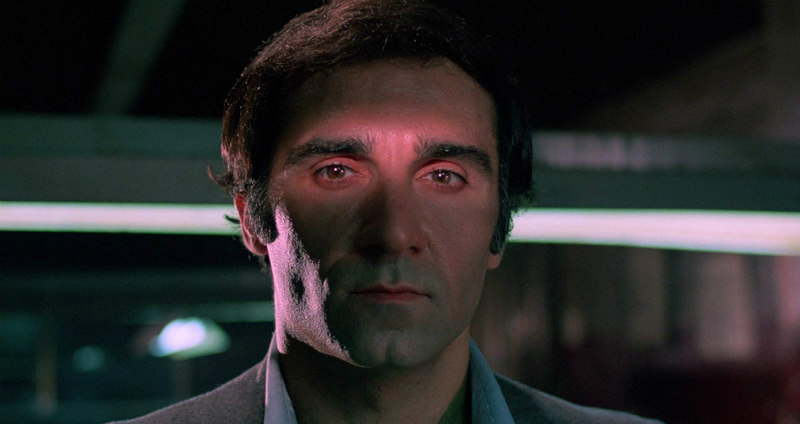

Along with revitalising old Hollywood masters, Cohen had a knack for recognising up and coming talent. The killer baby effects of It's Alive were the creation of a youthful Rick Baker, the FX genius behind the transformation scene of An American Werewolf in London, among others. For the lead role of a police detective suffering a spiritual crisis while investigating a series of spree killings in God Told Me To, Cohen cast Tony Lo Bianco, a vastly under-rated actor who had turned in scene-stealing performances in films like The French Connection, Serpico and The Seven-Ups. Hollywood had denied Lo Bianco the lead role he craved, but Cohen knew he was the perfect actor for his religious themed horror. Lo Bianco's performance in Cohen's film is as good as any turned in by his fellow Italian-Americans De Niro and Pacino during the '70s, and it's baffling how he didn't become a star on their level.

Shot on the never sleazier streets of '70s New York, God Told Me To is the ultimate Larry Cohen movie, and one of the great overlooked films of the '70s. In the movie, New Yorkers are going off on killing sprees, all claiming to have been visited by God, who instructed them to commit violence. Cohen really pushed the limits of what he could get away with in a city whose under-resourced police were too preoccupied with solving an unprecedented level of homicides to worry about low budget filmmakers stealing shots on crowded streets. The movie opens with an incredible sequence, shot during the Saint Patrick's Day Parade, in which, dressed as an NYPD officer, Andy Kaufman begins firing blanks into the crowd. Surrounded by armed cops, it's a wonder Kaufman made it out alive. Post 9/11, such guerilla filmmaking is simply no longer possible in an American city.

On 1982's monster movie Q: The Winged Serpent, Cohen would take advantage of Hollywood's overlooking of another great acting talent in Michael Moriarty. As a low-level hustler who holds New York to ransom after discovering the lair of the winged creature that has been menacing the city, Moriarty delivers a transcendant performance, one of the greatest seen in an American film of any genre.

Cohen and Moriarty would collaborate again on 1985's The Stuff, a satire of that decade's increasing commercialism. The film sees Moriarty play a former FBI agent hired by 'Big Ice Cream' to investigate the mysterious yogurt Americans have become addicted to. The Cohen/Moriarty collab would continue on sequels It's Alive III and A Return to Salem's Lot, the latter of which saw Cohen get to work with his idol Sam Fuller in an acting role that enlivens an otherwise misguided followup to Tobe Hooper's masterful mini-series.

In 1989, Cohen got to fulfil another personal dream, working with screen legend Bette Davis on comedy Wicked Stepmother. Sadly, the production led to Davis storming off the set. A problem with the aging star's dentures meant she was severely limited in how she could speak; unwilling to admit this, she instead blamed Cohen's direction. Despite being crushed by his treatment at the hands of his idol, Cohen turned the other cheek and refused to take legal action against Davis, who eventually admitted to the truth. Cohen wrote around Davis and managed to complete the picture, but with a heavy heart.

I often thought that with his New York sensibility and understanding of American pop culture, Cohen would have made a great Spider-Man movie. The closest he got was 1990's The Ambulance, in which Eric Roberts stars as a comic books artist investigating a series of disappearances involving a mysterious ambulance. Ahead of the curve as always, Cohen gave Stan Lee a cameo as himself.

Following '96's Original Gangstas, a love letter to the blaxploitation movies of the '70s with a cast including such stars of the genre as Pam Grier, Fred Williamson, Jim Brown and Richard Roundtree, Cohen stepped away from directing and found commercial success with his scripts for 2000s thrillers Phone Booth and Cellular. His final work as a director came in 2009, helming 'Pick Me Up', an episode of horror anthology series Masters of Horror. Fittingly, the episode saw Cohen reunite with Moriarty.

Hollywood, and indeed the world, is no longer accommodating of filmmakers like Cohen. We'll never see his like again, but there's a lot to be learned from his career. The internet is full of interviews with Cohen, who was as entertaining when discussing movies as when making them, and if you're considering a career in low budget filmmaking, I recommend you read, watch and listen to as many of them as you can find.

It feels like Cohen is gone too soon, that at 77, he may have had another script or two in him. But sadly, as a nurse in God Told Me To declares, "there's only one cure for old age."