After years of mistreatment by whites, an aborigine embarks on a murderous rampage.

Review by Eric Hillis

Directed by: Fred Schepisi

Starring: Tommy Lewis, Freddy Reynolds, Angela Punch McGregor, Ray Barrett, Jack Thompson, Peter Carroll

Many of the movies of the 1970s Australian New Wave dealt in allegorical fashion with that nation's colonial past, with movies like Wake in Fright, Picnic at Hanging Rock and Long Weekend painting a picture of Oz as a land unsuitable for habitation by white Europeans. There's nothing allegorical about Fred Schepisi's 1978 adaptation of Thomas Keneally's book The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith. This is as raw and uncompromising as cinema gets, a movie that has proven highly influential in recent years yet remains unmatched in its distinctively nuanced take on racism and its refusal to provide viewers with a one-dimensional hero.

Inspired by the true story of a 1900 massacre and subsequent manhunt, The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith's titular anti-hero, played by first-timer Tommy Lewis, is a mixed race aborigine taken in by a Methodist minister (Jack Thompson) and his wife, who have raised him in a manner that sees the young man treated with less contempt than a full-blooded aborigine but less respect than a family pet. Now in adulthood, it's time for Jimmie to set off into the world, find a job and settle down with a wife. Jimmie is advised to marry a white woman, as their children would then only be considered 1/4 black, their grandchildren 1/8 black and so on (breeding the black out of Australia was a popular policy at the time).

Jimmie marries the first white woman he comes across (and, indeed, comes in), Gilda Marshall (Angela Punch McGregor), a lowly servant girl. When she gives birth to a 100% Caucasian child, Jimmie realises he is not the father he had spent months assuming himself to be, and finds himself mocked even further by the whites he has come to live among. Through a series of occupations, Jimmie distances himself further from his aboriginal ancestry, even taking a job as a police constable, which sees him forced to brutally beat aborigines during a raid on a camp where a white man was killed after drunkenly causing trouble. Jimmie seems to take a relish in applying the kosh to his own people, as if enforcing a desire to beat the black out of himself. But no matter how hard he tries to impress, Jimmie fails to receive any respect from his white peers.

Things come to a head when Jimmie's younger brother Mort (Freddy Reynolds) comes to stay with him and help Jimmie with his work manufacturing a wooden boundary across acres of land. His employer refuses to pay Jimmie for weeks worth of work, claiming he has slackened off since the arrival of his brother and has turned his workplace into a "blacks camp." Desperate for food for his starving wife and child, Jimmie pleads for some flour from the wife of his boss, and when his pleas fall on deaf ears, he reacts with brutal violence, slaughtering the women and children he finds in his employer's home. Jimmie and Mort go on the run, with the former ditching his wife and child and declaring war on the white man, murdering the men who wronged him, along with their women and children, making him the most wanted man in Australia.

In the past few years, several movies have worn the influence of Schepisi's film on their sleeves. Quentin Tarantino's awful Django Unchained reworks Jimmie's story into a dumb-headed trashy revenge tale, with Jamie Foxx borrowing the mannerisms of Lewis and Tarantino ripping off a key image of blood spraying across a white surface; Jordan Peele's Us stages a scene in which a family, tellingly including obnoxious young twin daughters, is slaughtered in similar fashion to Schepisi's setup here; and Australian movies like Sweet Country and The Nightingale have similarly mined the violence of the colonial era. But what still sets Schepisi's film apart is its refusal to provide any easy answers. Despite how much time is spent explicitly detailing the despicable manner in which Jimmie is treated by both the upper and lower echelons of white society, it's impossible to justify his resulting murderous rampage. Most of Jimmie's victims are women, who were certainly guilty of treating him with contempt, but who equally are second class citizens in the Australia of 1900, and children, whose only crime was being born to colonial parents.

The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith isn't simply a straightforward revenge movie like those films it has subsequently inspired; rather it's a tragedy of a man whose spirit is broken so much that he loses his humanity, who becomes the savage he's been told all his life he really is. The smiling Jimmie we sympathise with in the movie's first half becomes a snarling, soulless brute, labelled a devil by his own kin.

Schepisi's film is a tough watch, and you may well need a shower after viewing. The violence has lost none of its shock value over the years, and Schepisi's staging gives it a hallucinatory feel that captures the mindset of the incensed Jimmie as he explodes with hatred. The first killing sees Schepisi employ his camera at a distance, which allows us time to watch Jimmie walk from one edge of the frame to the other, and as he makes the trek we're slowly gripped with the horror of what's going to happen when he arrives at his destination (inspired perhaps, by the killing of Martin Balsam in Hitchcock's Psycho?). It's a moment of filmmaking that suggests Schepisi would have made one hell of a horror director.

For all its unrelenting grimness, The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith has a streak of black humour running through its narrative. A scene in which a nebbishy liberal white school teacher makes a series of excuses for why he shouldn't be taken hostage by Jimmie is both hilarious and fraught with tension. A Greek chorus of sorts is provided by the intercutting of scenes involving Jimmie's prospective hangman in his day job as a butcher, shrugging off in deadpan fashion the questions of a customer who seems to have a disturbing fascination with the minutiae of the execution industry.

Shot over 5,000 miles of Australia's rugged terrain, The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith plays out its ugly human horrors against a stunning natural backdrop, all captured in striking fashion by cinematographer Ian Baker, whose work with Schepisi in this period (see also The Devil's Playground and Barbarosa) was the highlight of a career that later petered out in Hollywood mediocrity. A scene in which Jimmie comes across a sacred aboriginal site whose rocks have been covered in graffiti provides a startling image as horrific as any of his violence, hammering home the film's theme of a land desecrated by intruders.

Extras:

Eureka's disc lets you choose between Umbrella Entertainment's restoration of the 122 minute Australian cut or Shout Factory's restoration of the 117 minute International cut; commentaries on the Australian version by director Fred Schepisi and critic Alexandra Heller-Nicholas; interview with Schepisi; 36 minute Making-of doc; conversation with Schepisi and cinematographer Ian Baker; interview with actor Tom Lewis; Q&A session with Schepisi and actor Geoffrey Rush, from the 2008 Melbourne International Film Festival; documentary on the casting of Aboriginal lead actors Lewis and Freddy Reynolds; stills gallery; trailer; booklet featuring a reprint of Pauline Kael’s original review of the film.

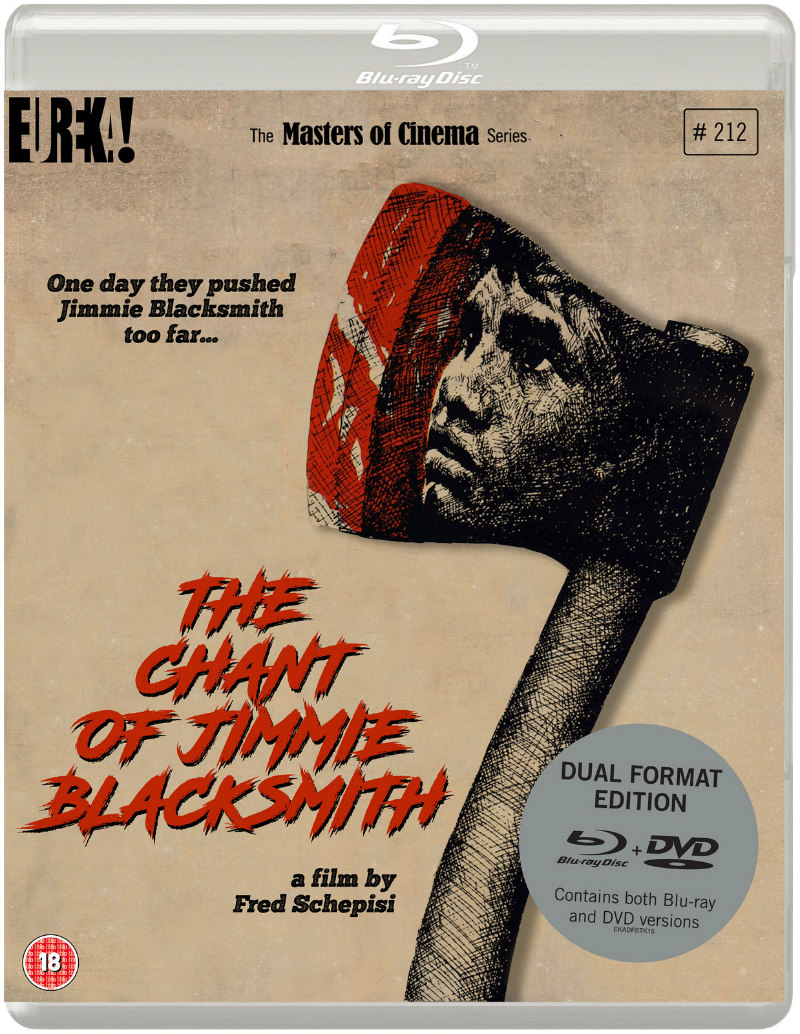

The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith is on dual format blu-ray/DVD August 19th from Eureka Entertainment.

"Given the Catholic Church's aversion to change, it's lost none of its impact over the decades."— 𝕋𝕙𝕖𝕄𝕠𝕧𝕚𝕖𝕎𝕒𝕗𝕗𝕝𝕖𝕣.𝕔𝕠𝕞 🎬 (@themoviewaffler) August 11, 2019

THE DEVIL'S PLAYGROUND (1976) is on DVD now from Artsploitation Films.

Read @hilliseric's reviewhttps://t.co/XggLYYphdl pic.twitter.com/0BD0ch3qYc