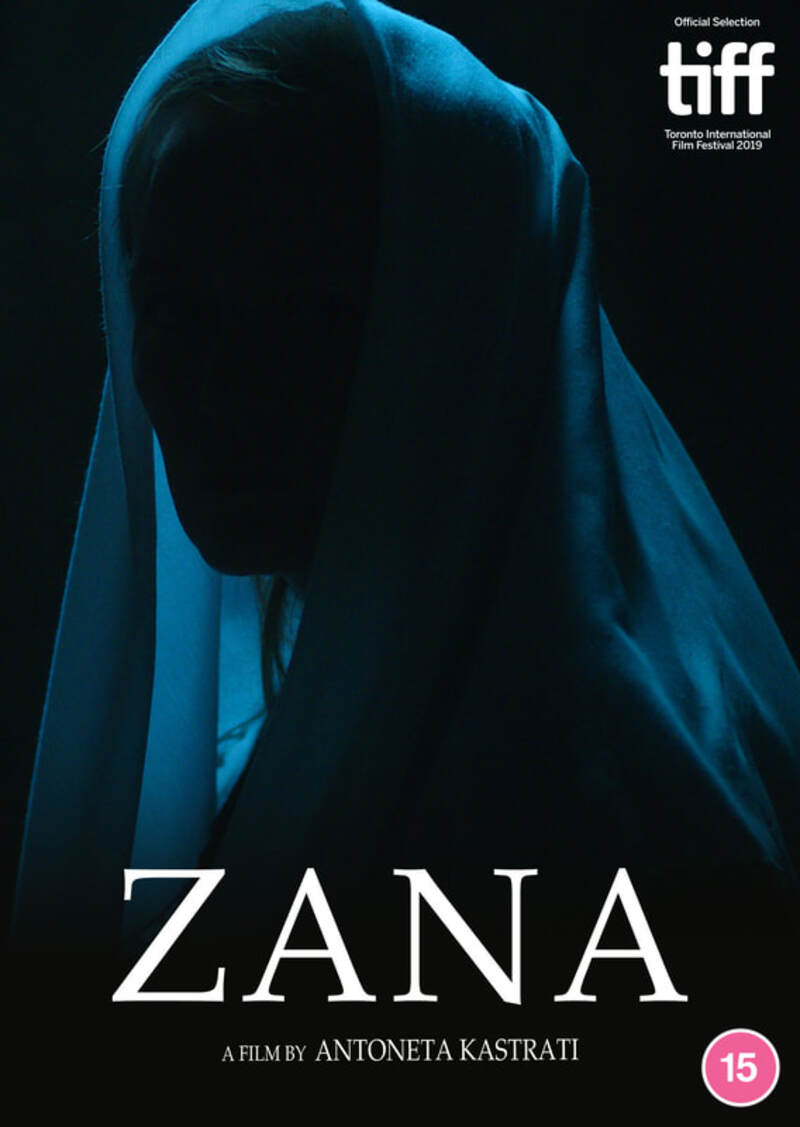

In rural Kosovo, a woman is pressured into turning to her village's witch

doctors in an attempt to treat her infertility.

Review by

Benjamin Poole

Directed by: Antoneta Kastrati

Starring: Adriana Matoshi, Astrit Kabashi, Fatmire Sahiti, Mensur Safaqiu, Irena Cahani

Last November, subhuman scum Hashim Thaçi, former guerrilla leader during

Kosovo’s war for independence from Serbia in the 1990s and the country’s

then president, resigned from office to face charges at The Hague for war

crimes and violations against humanity. The resignation wasn’t immediate:

an indictment was issued four months earlier, but shitbag Thaçi, riding a

wave of corruption and intimidation (NATO documents identify him as being

heavily involved with organised crime nine years before the indictment),

brushed off the accusations. That the trial has, however, become a reality

is hopefully an indication that the beleaguered republic is addressing its

awful past. The war for independence officially ended two decades prior,

but Kosovo has been shell-shocked and punch drunk since, with recent

atrocities not only defining the nation upon the world stage but also

abiding deep within the psyche of the populace.

In Antoneta Kastrati’s (with a co-writing credit to

Casey Cooper Johnson) poignant Zana we first meet our

protagonist Lume (Adriana Matoshi) leading a cow to a brook on the

Kosovan farmland where she lives and works circa 1999. The beast is

reluctant to drink from the water, and Lume turns her back in frustration

from the animal. In a shock non-linear cut, from Lume’s point of view as

she turns we see the decapitated head of the cow submerged in the shallow

brook, which is now slick with the sheen of fresh blood. Is this a dream,

a flashback, or actually happening?

The disorientation is illustrative of Lume’s post-traumatic stress; her

daughter was shot dead at some recent point in the past. Throughout the

film, Lume will return to this stream, and the body of water becomes an

abiding (and ultimately deadly) leitmotif throughout Zana, one that is increasingly denotative as it is as if Lume herself exists

underwater, disassociated from the world which is in flux about her.

It doesn’t help matters that Lume herself is offered similar regard by her

family in law as what they afford their livestock. They see her as a

heifer whose primary role is to breed. A persistent mother-in-law insists

on Lume’s pregnancy, and Lume’s dickhead husband is also set upon carrying

on the family line. Unlike his wife, he seems indifferent to his loss. The

implication is that Zana (the girl who died) was not ever as important as

a male heir, anyway. This is a patriarchal world, where men have status

and women are subordinate. Nonetheless, Kastrati outlines a bitter irony:

even though this society is overseen by men with guns - a character

remarks that ‘no one will take [a beaten wife], just older men’ - it is

women who get things done. Lume farms the land, tends to the animals,

chops wood; the mother-in-law is an overbearing matriarch who rules the

roost. In a rogue scene, Lume’s feminine strength (both emotional and

physical) resurges, when she knocks her fella to the ground with a couple

of punches (he was tauntingly threatening to go off with a younger woman)

and then effectively sexually assaults him into silence (not rape, btw:

the guy is mainly into it, just a bit scared of ‘being seen’ out in the

open, the big Jessie).

In the fragmented culture of Kosovo, Kastrati seems to suggest, fringe

beliefs and archaic misunderstandings proliferate within the cracks. Via a

visit to some conman mystic orchestrated by the mother-in-law, the family

begin to believe that Lume is possessed by a Jinn, and not, you know,

suffering from acute loss. The seriousness with which the family seize

upon the chancer’s diagnosis is scary, an all too convincing inversion of

the horror trope where the haunted woman is the last to be believed.

In another structural conversion, this time concerning narrative, the

numbing grief which Lume experiences is correlated with our growing sense

of dread throughout Zana: as the flashbacks culminate, we know that in this sincere and candid

film, before the running time is up, we will also witness the death of a

little girl, and there is nothing we can do to avoid this eventuality.

That there was nothing, despite her guilt, that Lume could have done,

either. In a title card which appears before the credits, Kastrati

dedicates her film to her mother and sister, Ajshe and Luljeta, who were

‘killed in the Kosovo war’.

Zana is on UK VOD from April 2nd.