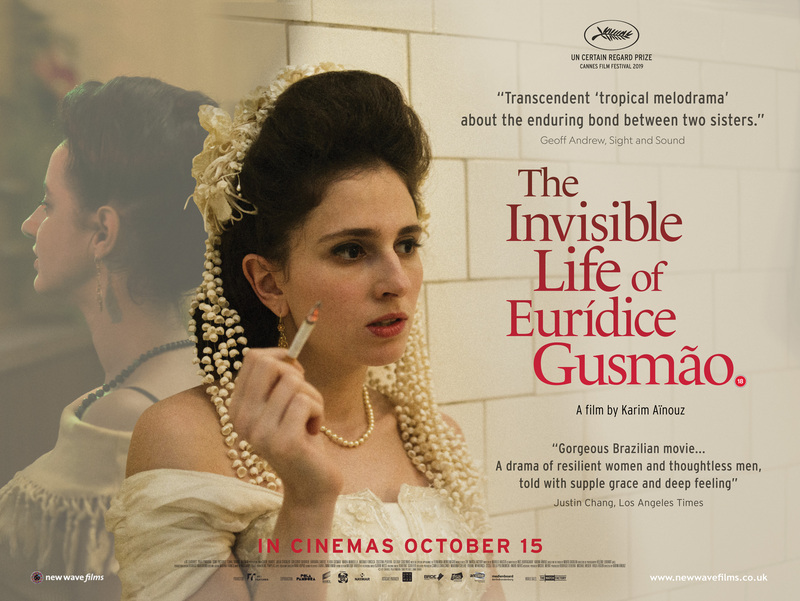

In 1950s Brazil, two young sisters are kept apart by their oppressive

father when one of them becomes pregnant.

Review by

Benjamin Poole

Directed by: Karim Aïnouz

Starring: Carol Duarte, Julia Stockler, Gregório Duvivier, Bárbara Santos, Flávia

Gusmão

Published in 2016, Martha Batalha’s

The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão, a magic realism inflected novel which looks at the social contexts of

1940s to 1960s Rio via the lives of two estranged sisters, generated a

critical commentary which focused on the novel’s presentation of the role

of women in mid-century Brazil, and the particularly crafted voice of

Eurídice, whose first person narration specified female experience. In an

author’s note, Batalha claims her fiction has a certain veracity, as

events are based on stories from her own family. Garlanded by Cannes where

it won top prize in Un Certain Regard, Karim Aïnouz’s (with

co-writing credits from Murilo Hauser and Inés Bortagaray)

gaudy melodrama adapts

The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão with an intriguingly

male gaze, transposing Batalha’s whimsy to a high camp as it relates its

narrative of Eurídice (Carol Duarte) and Guida (Julia Stockler), two sisters struggling against obstinate patriarchy.

With cinematographer Hélène Louvart, Aïnouz establishes a luxurious

visual dynamic in the film’s early scenes. On a deserted island where the

greying sea is reflected in the skin of frolicking lemurs, the palette

glows upon the screen, the colours saturated to a precise temperature of

lavishness. In the opening sequence, the women lose each other in the

island's forbidding landscapes of forests and cliff edges, their

diminishing voices calling out for each other as they get further away.

The fantasy sequence encapsulates what is to come, and while it does

honour the magic realism intonations of the novel, it also serves as an

introduction to the cinematic divergence Aïnouz intends: one of lush,

sumptuous visual sets and histrionic emotion.

At home in a cramped working-class apartment, both young sisters fantasise

of escape, with Eurídice investing in her burgeoning capabilities as a

pianist, while Guida is more simply propelled by youthful joie de vivre.

Guida’s lust for life sees her running away, shacking up with a Greek

sailor, and returning home when, following her pregnancy, the sailor skips

port. The girls’ father, a particularly strict and staid paterfamilias,

has none of it and throws Guida to the streets. Crucially, however, he

informs Eurídice that her sister has gone to live happily in Austria. What

follows depicts the girls growing into women separately, unaware that each

other are close by and facing similar struggles in different parts of the

city, with expository letters written and unread by the two.

The film posits that the women are individually sapped by their

estrangement, that sisterhood is a necessary bulwark against the crushing

male supremacism of 1950s Rio. Eurídice’s concerto dreams dwindle under

her father’s dismissive attitude, and, in time, Guida befriends an older

female sex worker who gives pragmatic support, but is cold comfort

compared to wide eyed Eurídice.

That the world Aïnouz creates looks so beautiful is an added malice, as it

is a milieu in which the two have no agency. The remove is most evident in

the jaundiced, and at times graphic, depiction of the sex each undergoes,

which is joyless and functional - a jaundiced representation of

heteronormative ruttings and rituals. This is a film made via the gay male

gaze: as if to underline the miserable functionality of straight sex,

Guida’s sex worker pal makes dismissive reference to ‘shitting out a

foetus’.

As ever, camp, an operatic heightening of everyday emotion, provides an

appropriate lens for this sort of material, because the form entails both

a recognition of how serious the business of being a loving, alive human

being is, but also how absurd the procedure is. ‘I’m terrified of

forgetting you’, one missive reads. Coolly aloof when not hysterically

passionate, The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão stops just

short of breaking your heart.

The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão is on MUBI UK now.