A young miner battling for worker's rights enlists the aid of a witch

doctor when he succumbs to a mystery ailment.

Review by

Benjamin Poole

Directed by: Kiro Russo

Starring: Julio Cezar Ticona, Francisa Arce De Aro, Max Bautista Uchasara, Israel Hurtado, Gustavo

Milán, Ricardo Aguilera

Is it me or is cinema, and films in general, getting a bit, well, boring

and safe? Various industry Cassandras (Richard Rushfield, my favourite gay

uncle Bret Easton Ellis) are heralding the death of cinema as we know it,

basing their doomy prognoses on the advent of streaming (which, according

to my daily mailshot from Finimize, may similarly be heading into a ‘bear

market’ - yikes) along with the detrimental impact of various lockdowns.

And aside from these injurious practical factors, there is the content

itself... Repeated IPs, franchising, remakes: watching trailer reels today

has a crushing over familiarity, and even the ensuing Twitter discourse

has a rinse/repeat insularity. It’s hard to get excited about the medium

in the way we used to. As I write, it is the Academy Awards weekend, and

while us lot will comment and riff and share thoughts, the idea of this

preening charade having any impact on the wider public is unimaginable:

who cares? Why should they?

The silver lining to this ennui, though, is the thrill one receives when

happening upon something which is highly distinct and actually, proper

good. Case in point, the joy involved in watching a screener of

The Great Movement, Kiro Russo’s undefinable movie concerning proletarian life in

Bolivia, and laughing along in wonder at the surprises and marvels within.

A master storyteller, Russo’s film opens in a long shot of El Paz; sun

worn and unbearably urban, a looming monster of glass, steel and brick

work. Non-diegetic sounds of the angry city - cars, building work,

concrete smashing - fill the soundtrack as we zoom in (god, I love the big

dick energy of a zoom) to our main characters, a disparate and rumpled

bunch of miners who are poor, caught up in a labour dispute and suffering

from the vicissitudes of the city’s unyielding societal structures.

Russo’s filmmaking is so animated and peculiar that the mind leaps for apt

comparisons. Here’s one: in high praise, the shots of the city, the

perfect immersion, the boots on the ground sense of ‘being there’,

reminded me of the wonderful NYC photography of

Larry Cohen. Here, La Paz is a city captured in full dusty, vivid motion. It’s not

just what Russo shoots, it’s how he films it, too. He has a magpie eye for

locating the third dimensions of a place that make it so substantively

tangible. Thus, we are alongside the miners knocking about in town,

arguing with a boss, and in one marvellously held static shot, having an

impromptu boogie in a bar. This established verisimilitude anchors the

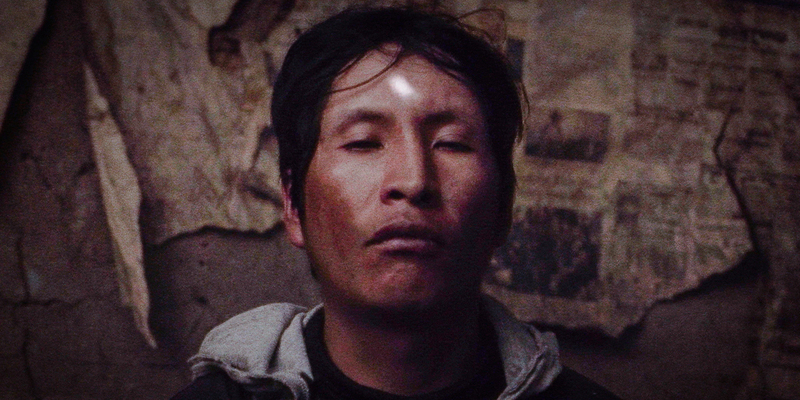

film as the loose narrative develops: our main character Elder (played by

Julio César Ticona, in a role apparently repeated from one of

Russo’s earlier films) has an ailment, for which he seeks out the services

of a witch doctor.

In this concise film’s second half, the narrative opens up into a pagan

panorama of occult imagery and sumptuous vistas of deep green and wild

nature: you can feel your lungs expanding with the powerfully placebo

effect. Yes, the contrast between primal nature and circumscribed

municipality is hardly a new observation, but the way in which Russo

relates his themes is entirely fresh and vital. This is a film where every

frame is reconsidered for ultimate photographic impact. And as

The Great Movement progresses, so does Russo’s visual

ambition, entering into the realms of perfectly portioned out magic

realism. For example, there is a scene where the doldrum market women, who

we have only previously witnessed selling the various produce which their

male counterparts have harvested, randomly break into a proper '80s style

choreographed dance routine - back lit alleys, dry ice - that had me

grinning in utter pleasure.

Eventually, however, visual dynamics and narrative playfulness is not

enough for Russo, and thus (inspiring another comparison, this time to

Švankmajer) the editing pushes moments together in a clumsy rush, the

frames are cramped on top of one another and begin to splinter, as if the

filmmaker is in frustration at the fundamental limits of the medium

itself. It is breath-taking and feels almost dangerous (it would be

irresponsible to wonder what watching The Great Movement in

an ‘altered state’ may feel like, with the stifling hyper-reality of the

everyday city in turn colourfully redeemed by flowing, psychedelic

spaces...). All this and a lovely white wolf, too.

The Great Movement is in UK cinemas

and VOD from April 15th.