Review by

Benjamin Poole

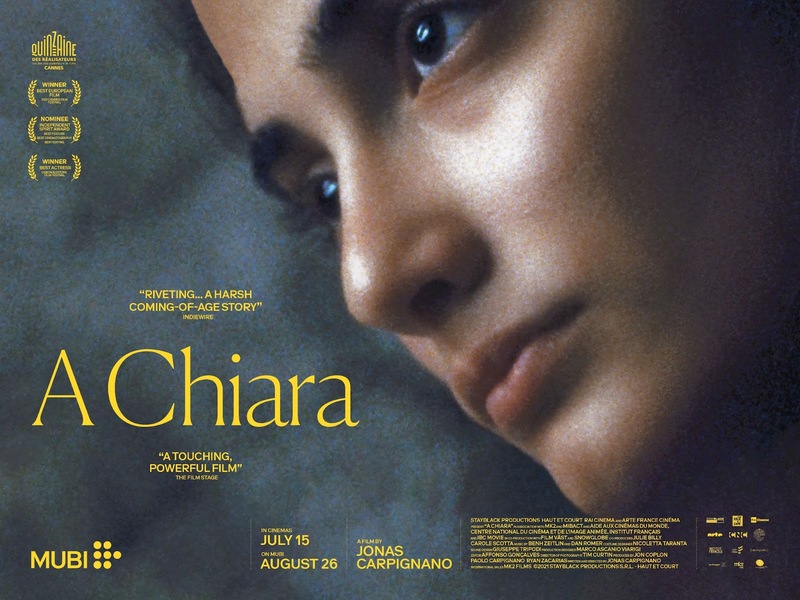

Directed by: Jonas Carpignano

Starring: Swamy Rotolo, Claudio Rotolo, Grecia Rotolo, Carmela Fumo

A cliché of the crime film, especially those which feature links to Italy,

is the prevailing trope of ‘family’: familial honour, familial bonds, the

aggrandizing implication that whatever wrongdoings are enacted in the name

of family are forgivable, and are, in fact, laudable. This always sort of

annoyed me, the glib glamourisation of bullies and criminals, who, when

contextualised within heteronormative nuclear families, are somehow

reconsidered as noble and aspirational. Do me a favour. These people are

the absolute worst! Facilitating their greed and will to power with

intimidation and violence and exploitation: a superstitious and cowardly

lot, indeed. Refreshingly, Jonas Carpignano’s

A Chiara reviews the trope of the Italian crime clan,

looking at the fallout of organised criminal activity as it affects a

kingpin’s family, in particular the titular Chiara, a 15-year-old school

girl (Swamy Rotolo) whose old man (Claudio Rotolo - yes,

they are real life father and daughter) has gone on the run after being

fingered by the law.

Apparently, Carpignano’s method was to work with the amateur actors of the

Rotolo family using an enigmatic, discrete manner: giving each performer

only the most scant information for a scene in order to elicit a

spontaneous, natural performance. Thus, A Chiara has high

levels of verisimilitude in its opening scenes as it immerses us in

Chiara’s world via non-causal sequences of her at the gym, the dinner

table, applying makeup. It’s all well and good, and the chemistry between

family members has a rare authenticity, but the approach is very

indulgent. A Chiara’s opening sequences, aside from the occasional enigmatic nods towards

the forthcoming second act revelation, are essentially a presentation of a

teenage girl’s rather quotidian lifestyle. There is an abiding sense that

representing a person’s daily presence is entertaining enough in itself:

this is meant to be narrative cinema, not Instagram.

Although, A Chiara hardly has the gloss which said platform

connotes. For all his crime affiliations, Mr Rotolo’s family abide on top

of one another in a cramped flat and live a rather utilitarian lifestyle.

Not that Chiara, or us, are meant to be initially aware of dad’s links to

the Calabrian underworld: it’s an interminable half an hour before

anything plotty occurs in A Chiara, so adherent is Carpignano to his scene setting. By then we’ve all

cottoned on to what’s afoot, apart from poor Chiara, whom we hang about

for, willing her to catch up. It’s a frustrating narrative choice: via

subjective framing, close ups, and long held shots on her looking a bit

pensive, we are encouraged to identify strongly with our central

character, but the sly dramatic irony contrasts the focus, further slowing

the film.

When Chiara finally catches herself on the film does tentatively approach

potentially interesting repercussions of the fallout. Notably, Chiara is

commandeered by social services, who attempt to move her across country to

live with a strange family; a measure ostensibly mooted to provide safety

for the girl, but which is really designed to put pressure on the exiled

Claudio. Makes you wonder who the real criminals are, etc, except it

doesn’t because the problem is, by this point, A Chiara has

run out of time to explore these intriguing viali. Chiara wanders around

in a fugue state of confusion, shifted about either by the authorities or

shady henchmen, demonstrating a lack of agency which belies the

self-actualisation of the film’s title. As an antidote to the disingenuous

aspiration of certain other mafioso depictions,

A Chiara does have worth, but, when it comes down to it,

this is an offer you might find easy to refuse.

A Chiara is on MUBI UK now.