Review by

Eric Hillis

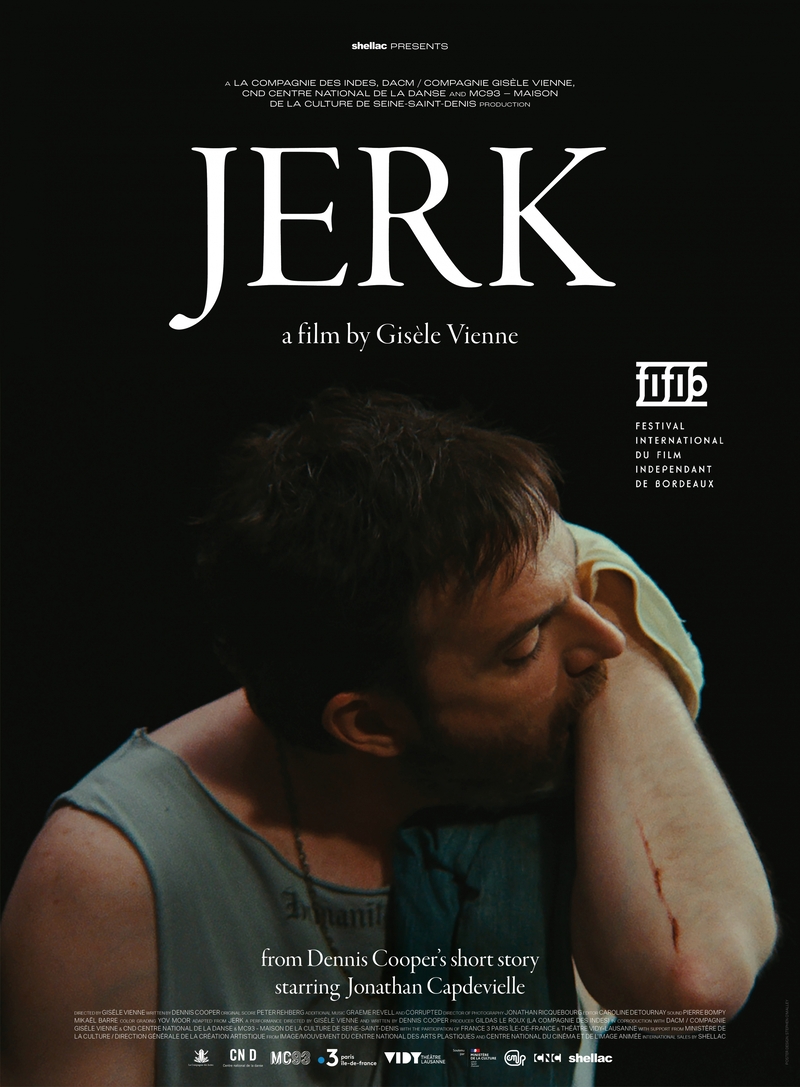

Directed by: Giséle Vienne

Starring: Jonathan Capdevielle

Between 1970 and 1973 Dean Corll tortured and murdered at least 28

young men in Texas. Corll, who came to be known as the Candy Man, was

aided in many cases by a pair of teenage accomplices – David Brooks and

Wayne Henley – until he was shot dead by the latter. In 1993 American

writer Dennis Cooper published Jerk, a novella based on the evil exploits

of the trio, and 15 years later adapted the story for the stage in

collaboration with director Gisèle Vienne and actor Jonathan

Capdevielle.

The play saw Capdevielle essay the role of Brooks, now several decades

into a lifelong prison sentence. As a (rather unlikely) form of

rehabilitation, Brooks puts on a puppet show in which he recreates the

crimes he committed with Corll and Henley.

Capdevielle returns to the role for Vienne's screen adaptation of Jerk.

Filmed in what appears to be a single unbroken shot, the movie sees

Brooks put his show on for a crowd barely glimpsed as blurry figures and

occasionally heard laughing uncomfortably during what constitutes the

"lighter" moments of the inmate's performance.

Brooks takes the role of himself, while using ventriloquism and puppets

to bring to life Corll and Henley, along with their victims. At first

the audience laughs at the sight of a puppet that looks a lot like the

star of some old kids' TV show essaying a serial killer, but any

uncomfortable giggling on the part of both the audience in the film and the

one watching Jerk itself soon gives way to discomfort.

Using his puppets, Brooks acts out unimaginably gruesome atrocities.

It's testament to Capdevielle's performance that we quickly forget we're

watching puppets. Brooks wants the audience to focus on his puppets, but

Vienne's camera tellingly focusses on the face of the human (or perhaps

inhuman) performer. This raises the question of where the audience of

the stage production centred their attention – on man or muppets? Did

they follow the character of Brooks' intention and watch the puppet

show, or did they succumb to Vienne's intention to watch Brooks himself?

One of the main things that differentiates cinema from theatre is that

the former gives the director greater power over what their audience

should be focused on, and Vienne forces us to watch Brooks as he

tortures himself by recreating his crimes in this odd manner.

Is it torture for Brooks or redemption? If it's the latter, does he

deserve redemption? As played by Capdevielle, the suggestion is that

Brooks is punishing himself with his performance in a way his

incarceration never could. In essence Vienne may have simply filmed her

play, but by centering the face of Brooks she employs one of cinema's

great advantages over the stage – the close-up. Watching Brooks wrestle

with his grisly memories makes for a deeply uncomfortable 60 minutes,

and Capdevielle is creepily convincing as someone who has engaged in the

sort of acts that fuel TV's True Crime industry.