Review by

Eric Hillis

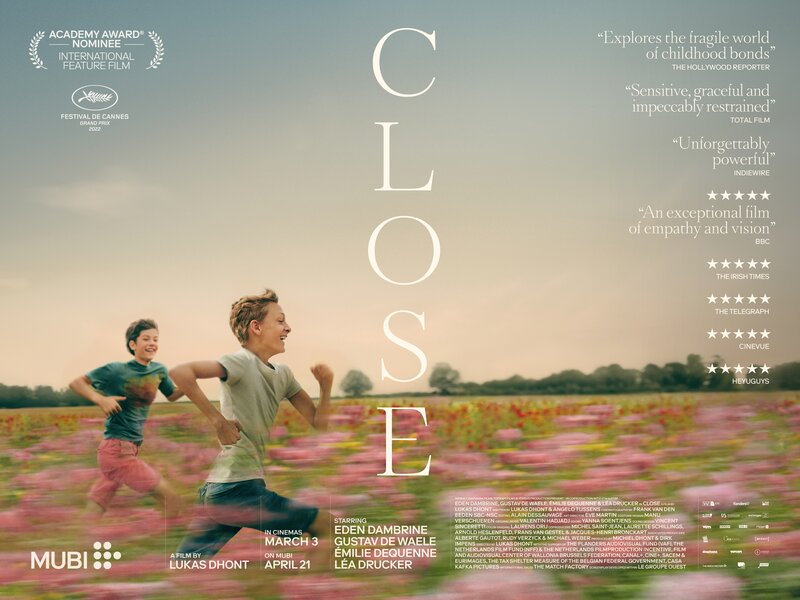

Directed by: Lukas Dhont

Starring: Eden Dambrine, Gustav de Waele, Emilie Dequenne, Léa Drucker, Kevin Janssens

Homophobia is unique among prejudices in that it can be weaponised

against anyone, regardless of their sexuality. You can't hurt a white

person by calling them the n-word, and someone with an athletic physique

is going to laugh off any attempts to call them "fat", but heterosexuals

can be taunted by homophobic slurs, and most have at some point. I'd

like to think things have changed as successive generations have gotten

more open-minded (Close suggests otherwise however), but

when I was a kid any young boy who indulged in an activity that wasn't

associated with an 18th century definition of masculinity immediately

had the f-word hurled at them. Listening to Whitney Houston? "F****t!"

Reading a book? "F****t!" And most ironically of all, hanging out with

girls? "F****t!"

In director Lukas Dhont's Close (co-written with

Angelo Tijssens), two young friends are torn apart by homophobic

taunts, and it's unclear whether either one of them is actually gay.

Maybe they both are. Maybe neither is. Maybe one is and one isn't. It's

irrelevant, as they're damaged by prejudice regardless.

13-year-olds Leo (Eden Dambrine) and Remi (Gustav De Waele) enjoy, as the title suggests, a close friendship. Inseparable during

their summer holidays, they spend every waking minute together, and when

they're not awake they're sleeping in the same bed. So close are the

boys that it's almost as if they each have two sets of parents, as Leo's

mum (Lea Drucker) and dad (Marc Weiss) treat Remi as

though he were their own son, while Remi's parents (Emilie Dequenne, Kevin Janssens) have a similar relationship with Leo.

The boys' innocence is shattered when they enter Belgium's equivalent

of high school. Initially delighted that they've been put together in

the same class, Leo and Remi's closeness is immediately picked up on by

the sort of kids who need someone to target. Between girls asking if

they're a couple, in a manner that suggests not malice but genuine

curiosity, and boys hurling around homophobic slurs, Leo decides if he's

to survive high school he should probably put some distance between

himself and Remi. He joins the hockey team in an attempt to prove his

masculinity, and stops calling over to Remi's house. This deeply hurts

Remi, and with the boys unwilling or unable to discuss the issue, it

leads to the inevitable playground brawl.

This portion of Dhont's film plays in similar fashion to another

similarly themed recent Belgian drama, Laura Wandel's

Playground, in which a young girl distances herself from her older brother upon

realising he's been marked by the school bullies for a campaign of

torment. This is by no means a phenomenon unique to Belgian schools, but

it is interesting how two Belgian filmmakers decided to explore the

concept at the same time (perhaps Belgian readers can tell me if there

was some specific incident of bullying that made the news there in

recent years?).

Close is truly heartbreaking, and there's something about

seeing a platonic friendship end in this way that's far more affecting

than the collapse of a romantic relationship. In their screen debuts,

Dambrine and De Waele prove themselves remarkable young talents. The

latter is asked to evoke our sympathy, which he does in such a

convincing manner that you want to reach into the screen and give him a

reassuring hug and lie to him about how it's going to be okay. Dambrine

has a somewhat more difficult task in provoking both ire and empathy

from the viewer, but he truly sells Leo's mix of guilt and

confusion.

[Spoiler] The marketing has kept a key

plot development secret, so turn away now if you wish to have it sprung

on you as a surprise. Halfway through the movie Leo learns that Remi has

taken his own life. Convinced, rightly or wrongly, that he is to blame,

he spends much of the remainder of the movie wandering in an existential

fugue. He's desperate to confess his perceived sin to Remi's mother, but

can't bring himself to do it. Dequenne delivers such a tender portrayal

of a grieving mother that we can understand his reluctance to add to her

hurt. After all, she's told Leo she thinks of him as a second son –

wouldn't it be cruel to take that away from her? A cliché of European

cinema over the last couple of decades has seen characters attend

classical musical performances and stare into the abyss as sombre music

plays. It pops up once again here in the form of a school recital, but

it has extra weight here as it's a performance at which Remi, a talented

flautist, should have been taking centre stage. As Leo watches the blank

expression of his late friend's emotionally numb mother, our hearts ache

for their respective torment.

I imagine any parents who watch Dhont's devastating drama may start

paying slightly more attention to their own children. Filmmakers can

often over-estimate the importance of their work, but if

Close causes one parent or teacher to step in before

tragedy strikes, it will be the most important movie of the year.