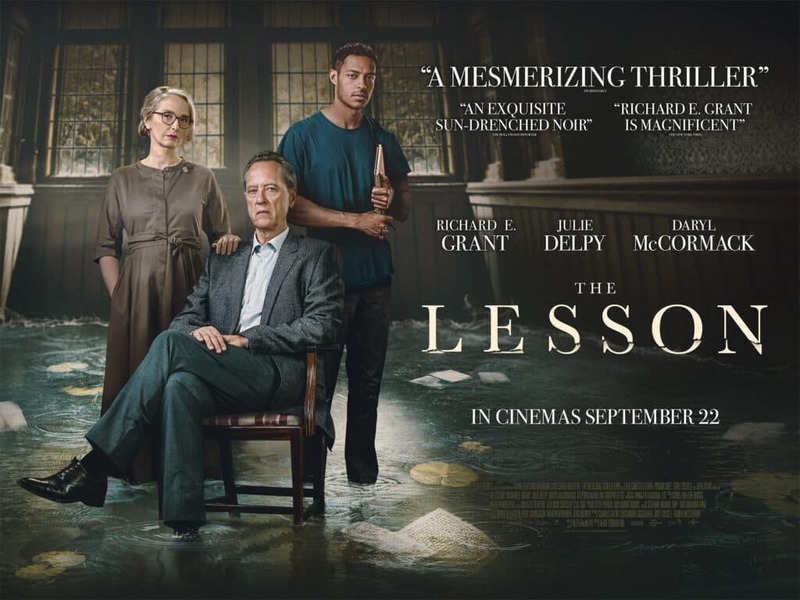

An aspiring writer uncovers intrigue when he accepts the role of tutor to

the son of his favourite author.

Review by

Eric Hillis

Directed by: Alice Troughton

Starring: Daryl McCormack, Richard E. Grant, Julie

Delpy, Stephen McMillan, Crispin Letts

Continental European thrillers have long drawn inspiration from

Britain. The German Krimis of the 1960s were mostly loose adaptations of

works by Edgar Wallace. The Italian Gialli of the '60s and '70s were

inspired by the popularity of classic English whodunits, reissued in

Italy in distinctively lurid yellow-bound paperbacks. French filmmakers

have always been drawn to adapting British crime fiction, much of which

is overlooked in its own country. It's very much a one-way street, as

British cinema rarely draws inspiration from the continent.

Alice Troughton's feature directorial debut

The Lesson is a British movie that does feel influenced by

Europe, specifically France. That's to say that at its best it resembles

the work of Ozon, Chabrol and Becker. You might even be fooled into

believing it's a remake of a French movie adapted from some forgotten

British novel. The French actress Julie Delpy is cast in just the

sort of role a French filmmaker might give to an English actress like

Charlotte Rampling or Kristin Scott-Thomas.

A lot of French thrillers don't really become thrillers until their

final acts, and the transition isn't always successful. They tend to

play better as character dramas, as battles of wits and psychological

powerplays, and they become less interesting when a corpse is eventually

discovered. That's an issue The Lesson shares with its

French cousins. For its first two thirds it's a gripping character

drama, a fascinating battle of wits and an intriguing psychological

powerplay. But then it becomes a thriller in its final act and much of

its good work is undone.

This is largely intentional on the part of Troughton and screenwriter

Alex MacKeith. Their film is broken into three distinct parts

marked by intertitles. Troughton and MacKeith want the viewer to be

acutely aware of their film's final act shift. It might be a case of

filmmakers being a little too clever for their own good.

At one point our protagonist, young writing tutor and aspiring novelist

Liam (Daryl McCormack), gives a critique of the long awaited

comeback novel of his literary hero, author JM Sinclair (Richard E. Grant). He offers that he loves the work, but that it's let down by a final

act that feels like it belongs to a different book. Such self-awareness

renders much of my critique null and void.

Liam finds himself in the company of Sinclair when he is hired by the

author's wife, French artist Helene (Delpy), to tutor their teenage son

Bertie (Stephen McMillan), who simply must get into Oxford's

English Literature programme. Whether Bertie actually wishes to follow

his father's footsteps is another matter however, and the boy reacts

sullenly to Liam's intrusion. There's also the metaphorical ghost of

Felix - Bertie's older brother, who drowned himself in the estate's pond

- hovering over proceedings.

Liam is initially ignored by Sinclair until he proves himself useful by

fixing his temperamental printer. The cantankerous author is also

impressed by Liam's ability to store entire volumes of literature in his

head. It's a skill he claims isn't a photographic memory but rather a

reaction to words. When the two men agree to read and offer mutual

critiques of their latest work, the stage is set for a potentially

fraught scenario. Liam is probably happy enough to learn how bad his

writing is, but Sinclair has only ever been told how great a writer he

is. This can't possibly end well.

Much of The Lesson plays out as a classic joust between a

person of power and an underling desperate to get some of that power for

themselves. If you've seen the likes of Damien Chazelle's

Whiplash or Alain Corneau's Love Crime (one

of the best French thrillers to cast the aforementioned Scott-Thomas as

a villainess), you'll be familiar with how this dance goes. Sinclair

almost seems to get off on subjecting Liam to a variety of

micro-aggressions and outright cruelty. The younger man largely soaks it

all up, possibly because like any writer he's dogged by insecurity, but

possibly because he has ulterior motives.

McCormack delivers a striking star-making turn that sees him turn on

the charm while also coming off as a little creepy. We're never quite

sure what to make of Liam, who might be the victim or the perpetrator

when the story ultimately reveals itself. Casting a black Irish actor,

and allowing him to keep his accent, adds an extra dimension, creating

an unspoken tension between this self-educated working class product of

two colonised cultures and the English and French toffs whose domain he

now finds himself in. Liam walks around the estate with his hands

constantly by his side, as though he's worried he might break something

he couldn't possibly pay for. I'm not sure if Troughton is actually

aware of this dynamic (McCormack's presence is likely a piece of

colourblind casting), but it's clear that McCormack certainly is, and is

likely drawing on his own experience of being thrust into the very white

and upper middle class world of the arts. Liam spends a lot of time

awkwardly standing outside rooms, but McCormack's ambiguous body

language leaves room for interpretation – is he waiting uncomfortably to

be invited in or snooping and gathering evidence?

A shame then that so much of this good work is undone by a final act

that takes the film into thriller territory. The shift never feels

organic, and like

Get Out, it relies heavily on a white antagonist clunkily explaining the plot

to the black lead. Yes, the shift is clearly intentional and all very

meta, but it could have been handled in more confidently cinematic

fashion.