Review by

Eric Hillis

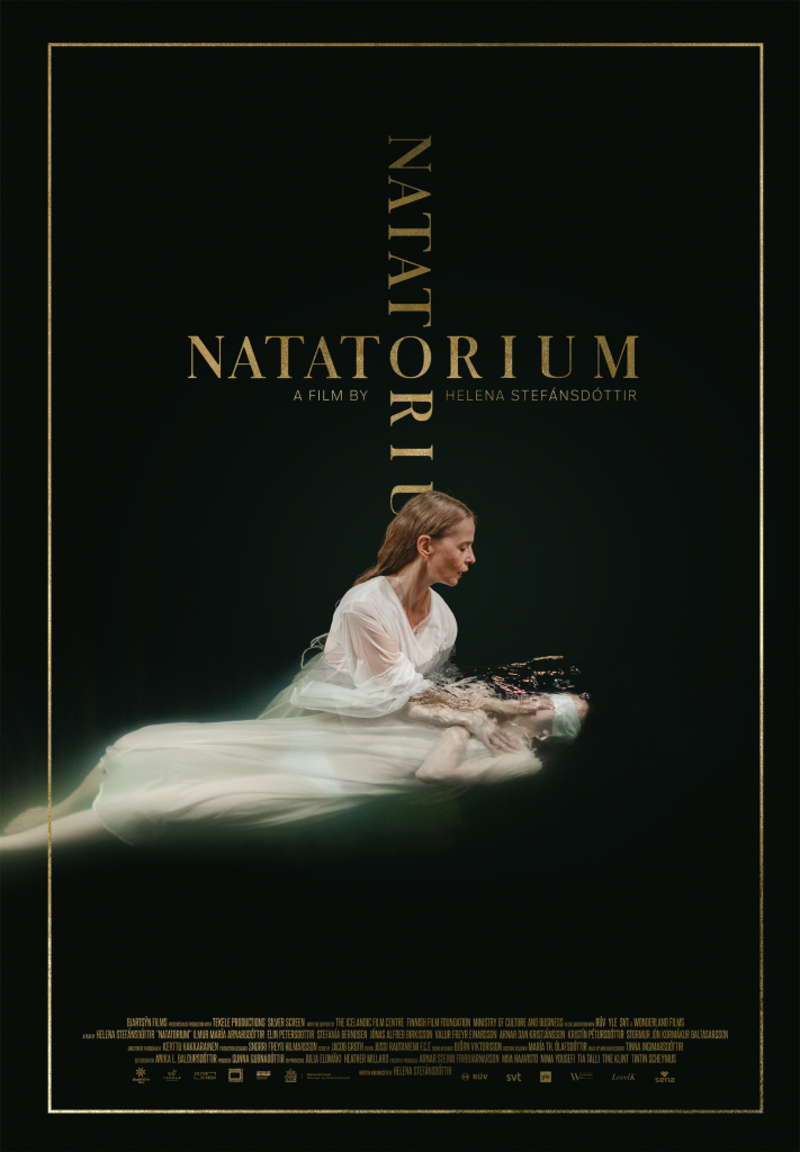

Directed by: Helena Stefánsdóttir

Starring: Ilmur María Arnarsdóttir, Elin Petersdottir, Stefania Berndsen, Jónas Alfreð Birkisson, Valur Freyr Einarsson,

Arnar Dan Kristjánsson

Ever since 1942's Cat People, the makers of horror movies and thrillers have been incorporating

swimming pools into their work. Horror movies like Sinister,

It Follows, The Final Destination, Let the Right One In and

A Nightmare on Elm Street 2 have featured sequences

utilising pools while thrillers like Deep End, Swimming Pool and Swimfan have made

central plot elements of pools. John Badham swapped

Les Diaboliques' famous bath tub for a college pool in his American remake

Reflections of Murder. 2024 has given us

Night Swim, a hokey supernatural thriller about a haunted pool.

What is it about the swimming pool that makes it such an ominous device

in movies? Perhaps it's because it's an attempt to control nature, a man

made structure that is still privy to the untameable wrath of nature. Or

maybe it's the seductive side of the pool. How many movies have featured

scenes in which temptresses coerce men into joining them in a pool with

siren-like beckoning?

Icelandic thriller Natatorium draws on both these ideas

to some degree. It features a swimming pool that played a role in a

death which may not have been entirely accidental. It's also used by

women to lure their prey. 18-year-old Lilja (Ilmur María Arnarsdóttir) uses the pool in question here to seduce her boyfriend (Stormur Jón Kormákur Baltasarsson). Her grandmother, Arora (Elin Petersdottir), uses it to beckon

Lilja towards some uncertain fate.

In order to attend a musical audition in the city, Lilja stays with her

grandmother and grandfather (Valur Freyr Einarsson), whom her

father, Magnus (Arnar Dan Kristjánsson), has kept her away from.

When Magnus learns Lilja has visited his parents behind his back he

panics and calls his sister Vala (Stefanía Berndsen), who is

equally alarmed and rushes to persuade Lilja to stay with her instead.

Lilja dotes on her grandparents however and refuses to leave.

When Lilja discovers there's a swimming pool in the basement of her

grandparents' home, which her grandmother bathes in every night, she

initially uses it to frolic with her boyfriend, unaware that she's being

watched by Arora (Petersdottir's resemblance to Charlotte Rampling makes

it impossible not to recall Francois Ozon's

Swimming Pool in this moment). That the religiously devout

Arora is fine with this sort of thing going on under her roof is the

first hint that she may have sinister intentions towards her

granddaughter.

Arora's living room features a shrine to her daughter Lilja, who

drowned in the pool as a child, and for whom her granddaughter was

named. The shrine is decidedly Catholic, but we also see Arora dip Lilja

beneath the pool in the manner of the Baptist church. The suggestion is

that Arora has experimented with several varieties of faith to deal with

her grief. Might she also be willing to indulge in some darker beliefs?

There's talk of how Friday the 13th began as a Nordic celebration of

female power before Christianity gave it a sinister, superstitious

association. This invocation of Norse paganism raises the idea of the

blót, the Viking tradition of sacrificing animals and humans to appease

Gods, a ritual often held in bodies of water. Arora's other son, Kalli

(Jónas Alfreð Birkisson), is bedridden in a sickly state. Vala

argues that he belongs in a hospital, but Arora insists on keeping her

in her home, but to what purpose?

The Nordic countries represent arguably the most atheistic region of

our world, and yet many of its films have a spiritual undercurrent. None

of the characters in Natatorium explicitly raise the idea

of pagan sacrifice, but it's an unspoken fear that permeates through the

film. Director Helena Stefánsdottir stages a dinner celebration

by positioning her camera in the centre of the dining table and panning

slowly across the faces of the assembled characters. With each circuit

of the table we see rising apprehension on the faces of Lilja's family

members as they come to realise the danger this young member of their

brood might be in.

We never hear anyone speak of what Anglo-Saxon folk-horrors might call

"the old ways," but we see the reaction on the faces of people who have

made discoveries offscreen. Stefánsdottir takes a similar approach to

the world of her film as Demián Rugna with his Argentine chiller

When Evil Lurks, dropping us into a world where people live with the accepted fact

that dark forces surround them, and leaving it to the audience to catch

up.

Stefánsdottir only begins to delve into her film's folk-horror aspects

as it moves towards its conclusion however, with most of the movie a

rather grounded familial mystery. It's never quite as effective as it

promises, chiefly because the threat to Lilja is so ambiguous that

there's very little opportunity to build suspense. We get the sense that

Lilja is in danger in the grand scheme, but she's never placed in the

sort of situations that might make us apprehensive for her safety in the

moment. Natatorium may prove more effective on a second

watch, when the viewer has a greater idea of what exactly is at play

here, but its frustrating refusal to explore its themes more openly make

it unlikely to entice many viewers back for a second dip in its icy

narrative waters.