A Congolese emigrant is confronted with his culture's superstitions when

he returns home from Belgium with his pregnant white girlfriend.

Review by

Benjamin Poole

Directed by: Baloji

Starring: Marc Zinga, Lucie Debay, Eliane Umuhire, Yves-Marina Gnahoua

Belgian rapper Baloji, the mononymic writer/director (with script

help from Thomas van Zuylen) of Omen (not that one,

etc), is a force to be reckoned with. Awarded platinum records as a

musician in his late teens, and following a few well received acting

roles along with directing an experimental short film, this year the

auteur's feature length debut was selected as the Belgian entry for Best

International Feature Film at the Oscars. Fair play. Baloji's work often

draws upon his heritage and his familial relationships, with the

rapper's first solo album 'Hotel Impala' (2008, composed after he won a

national poetry competition-!) dedicated to his mother whom he had not

seen for over two decades (she "did not really understand it," the

rapper lamented). The strange, sometimes toxic, bonds of family and the

intractable shadow of identity are ideas Baloji has returned to

throughout his oeuvre and are explicitly explored within the vivid

mise-en-scene and kaleidoscopic narratives of Omen.

Omen's dominant story focuses on Koffi (Marc Zinga) and Alice (Lucie Debay), who are a good-looking young couple living in Belgium. Expecting

twins (aww!), the two want to get married, yet, due to the mandates of

Koffi's Congolese heritage, such a union entails a visit back to the

Congo for the approval of his family, a formality underlined by the

€5,000 dowry Koffi must give his dad. It probably doesn't help matters

that Alice is white, either...

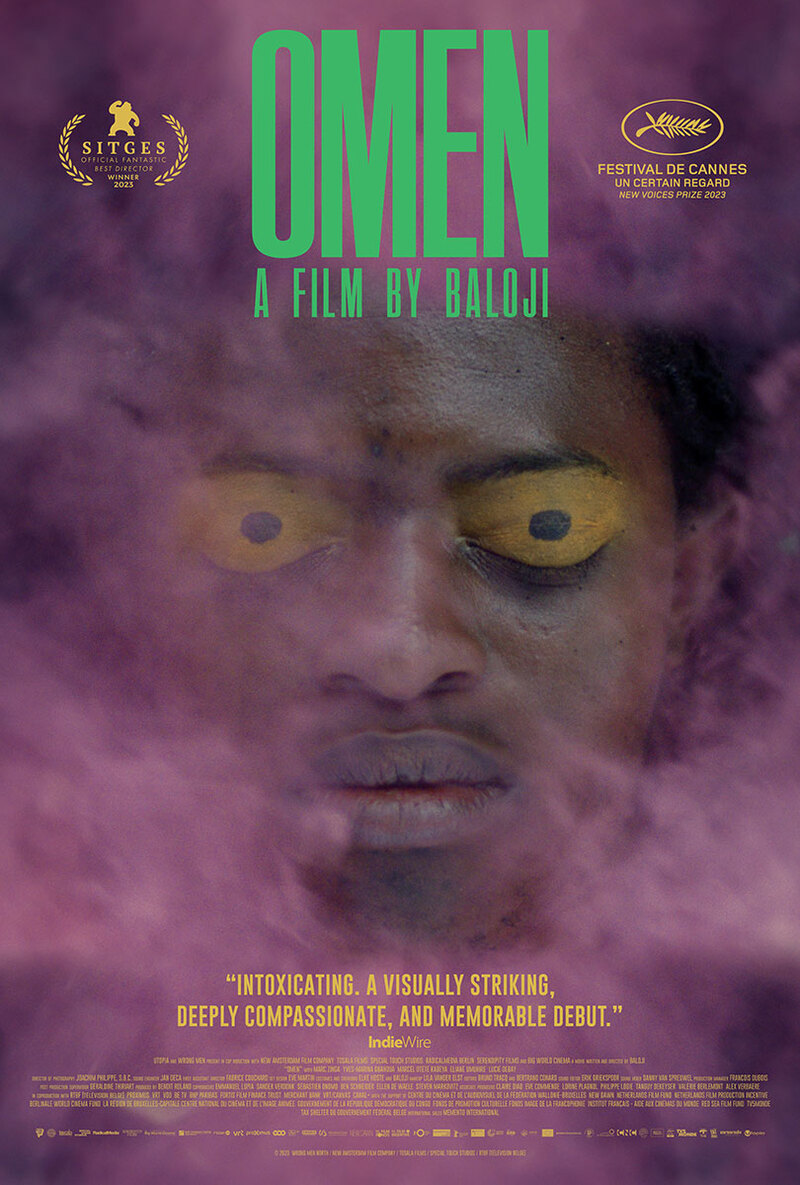

The film opens upon a non-sequitur set within a burned desert of

scarecrows, wherein a mysterious figure expels lilac hued breast milk

into flowing water (I'd say it's not something you see every day, but I

watched

Sasquatch Sunset

with its violent lactation just last week...) establishing

Omen's characteristic visual language of symbolism and colour and preparing

us for its at times abstract approach. We then cut to the stark image of

Koffi facing us in close up, his afro dissected like that poor tree at

Hadrian's Wall. Before the fade in on Koffi, the film's first dialogue

comes from Alice: "It saddens me to cut your Afro," she says, while

Koffi stumbles to explain that he's doing it in prep for the forthcoming

family visit. A montage of Koffi combing his freshly shorn head and

practising what he is going to say to his Congolese kinspeople follows.

The display of male vulnerability, of reluctant duty to keep up

appearances, is a paradigm which Omen returns to in its

second interwoven story, which features street gangs of teenage boys;

one of the groups is seemingly opposed to gender conformity and knock

about in uniform pink dresses to honour of the death of their leader's

sister.

A final supplementary story features Koffi's own sister Tshala (Eliane Umuhire), who wants to move to South Africa in order to be with her boyfriend,

a process complicated by the inconvenience of an STD which was received

courtesy of his infidelity. In the same way the complementary hues of a

rainbow reinforce each other, the storylines of

Omen cooperate to throw light on the film's deeply

personal themes. It is fitting that a film so visually dynamic should be

sub-textually concerned with how we present ourselves to others, and how

others perceive us, regardless. Narratively, each thread shares the

worst-nightmare situation of frustration, of not getting anywhere

against punitive odds. When Koffi and Alice do arrive at the homestead,

the extended family seem disinterested in the return of their

son/brother and dismiss him with the childhood nickname "Zabalo", which

means "mark of the devil" - charming! The family are more interested in

a sister's new-born baby (boring), and when Koffi, holding the infant,

accidently nose bleeds on it, it all kicks off. Like, properly kicks

off: Koffi is subject to a brutally enacted spiritual ritual, involving

elaborate costumes and a helmet placed over his head, which is duly

macheted into. The shift in tone is so sudden and scary that you don't

have time to fully comprehend the absurdist implications until later: if

Koffi's family have all of this gear, and a "trial room" already set up,

then they must do this sort of thing regularly... No wonder Koffi moved

to Belgium, and perhaps understandable, too, that he feels he should

achieve some sort of closure before the creation of his own

family.

Despite its short running time it is impressive how richly detailed

Omen feels, how it so efficiently builds a world with

performances and direction that emotionally convince, even when the film

dips into dreamlike magic realism. Omen offers that same

off kilter quality that often occurs when artists from other disciplines

make films; David Byrne's True Stories or Prince's vanity

projects, say. There is an outsider perspective to such product, a

specific vision which is borne from an explicitly artistic intention,

even when the end products are hit and miss. In the case of Baloji's

Omen and its truly idiosyncratic nature, the hits keep on

coming.

Omen (Augure) is in UK cinemas

from April 26th.