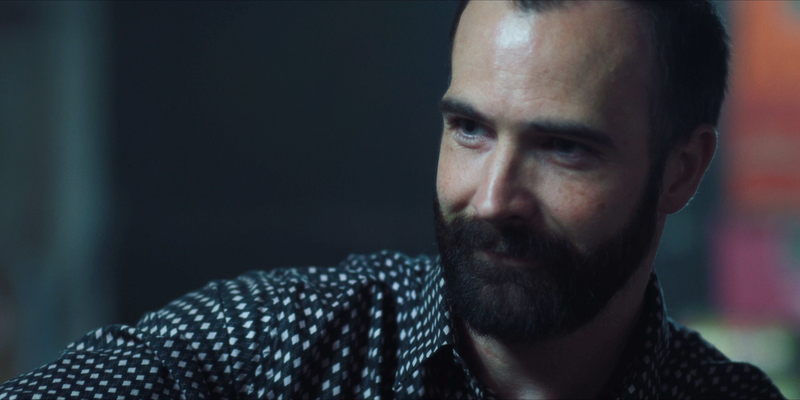

A recovering addict from a deprived Liverpool estate attempts to realise

his dream of becoming an actor.

Review by

Benjamin Poole

Directed by: Melanie Manchot

Starring: Stephen Giddings, Michelle Collins, Michael Starke,

Kent Riley, Paislie Reid, Thomas Sweeney

Couldn't have been more than five minutes ago I was scrolling Twitter

and up came a post from @ScrtDrugAddict asking "Is life just switching

addictions until we die?" Now, I don't follow the account - the tweet

appeared on the "for you" feed - but it turns out that perhaps

there is something in the pernicious algorithms of the platform, as the

plaintive rhetoric of the question certainly struck a chord with me - a

person of, if not addiction, then certainly obsession. What is existence

without mania? What is life without an abstract to devote it to? A void,

I reckon. Although you do begin to worry, don't you, about the point

where benignly doing something you like a lot curdles into a habit: a

pursuit that is joyless but an intrinsic aspect of your being. The knife

edge where perfecting the vodka martini becomes alcoholic dependency;

when a relationship becomes toxic; of what happens a week after people

begin smoking cigarettes. Or, accordingly, the most addictive pursuit of

all: gambling.

It is easy to understand why gambling is so enthralling. So much going

on with the buzz of the risk, the cruel hope, the sense that the odds

can be overcome. There no such thing as a sure bet and so the rush is in

the process. Unlike the repetitive impulse of drugs, the experience of

gambling is always dangerously fresh and exciting, and even worse, tied

into potential answers for the same dire situations which the addiction

has caused. Drugs may be a release, but the big score can be a

solution... (I'm saying all this having hardly ever gambled in my life

and only then on Eurovision, but there is a disastrous history of it in

my family, so I have thought about it a lot over the years if that

counts). It is disingenuous that mainstream cinematic depictions of

gambling are often constructed within glamourous contexts (Vegas, etc),

with attendant iconography of poker tables, chips, big wodges of cash:

the inherent risk of the process is a Todorovian structure within

itself, too (I knocked

Molly's Game

on last night - where big game poker is a backdrop for Jess Chastain's

Hollywood actualisation). A representation far removed from the lived

experience, which is scarcely presented within narrative cinema.

Melanie Manchot and co-writer Leigh Campbell's fiercely

original Stephen is however a profoundly intelligent,

effective and challenging portrayal of gambling, along with the social

ills inevitably associated with the addiction. The film eschews typical

narrative structures, and instead affects a montage of historical

footage, documentary style and re-enactment to retell the story of

Stephen Giddings (the actor) as he auditions for the part of

Thomas Goudie, the subject of the very first filmed crime

reconstruction. A Brechtian rug is first pulled in the post title

sequence wherein we painstakingly follow Stephen (a Merseyside Will

Arnett) through the council estate where he lives to the local dive bar

to watch him compulsively deposit coins into a fruit machine. After a

set-to with another character, the camera turns to reveal a panel of

filmmakers, who comment on his performance – "What you did earlier with

the fruit machine was brilliant." The character-within-the-story becomes

the character-of-actor-within-the-enveloping-narrative: a mimetic

overture compounded by the filmmakers' use of amateur performers and

real-life addicts.

Manchot is careful in her presentation of this sensitive material, never

sensationalising her ersatz cast and instead creating a platform for

these voices, including professional actors such as

Thomas Sweeney (who also shares his experience of alcoholism

within the filmed group sessions - when you're an alcoholic a bar is

"like a Christmas tree"). The switches between documentary

verisimilitude and constructed narrative are deliberately

disorientating, especially so as the sequences with Stephen as

character are so emotively involving (I'm thinking of a horribly

convincing fight over a fruit machine...). During

Stephen we find ourselves dramatically gripped as Stephen

slips further and further into hot water, yet also challenged by the

otherwise objective portrayals and their purposeful lack of easy

sentiment.

It is a heady mix, and one which thrills with its bravura creativity. An

artist by profession, Manchot's film has the multi-media mien of an

installation piece, where the meta lens is a cracked mirror, reflecting

the complex and frustrating experiences of those at the hard end of

addiction. At times there are certain flourishes that detract from its

overall impact, such as cutaways to superfluous interpretive street

dance, but beneath Stephen's shifting layers of fact and fiction beats a deeply compassionate

heart.

Stephen is on UK/ROI VOD now.