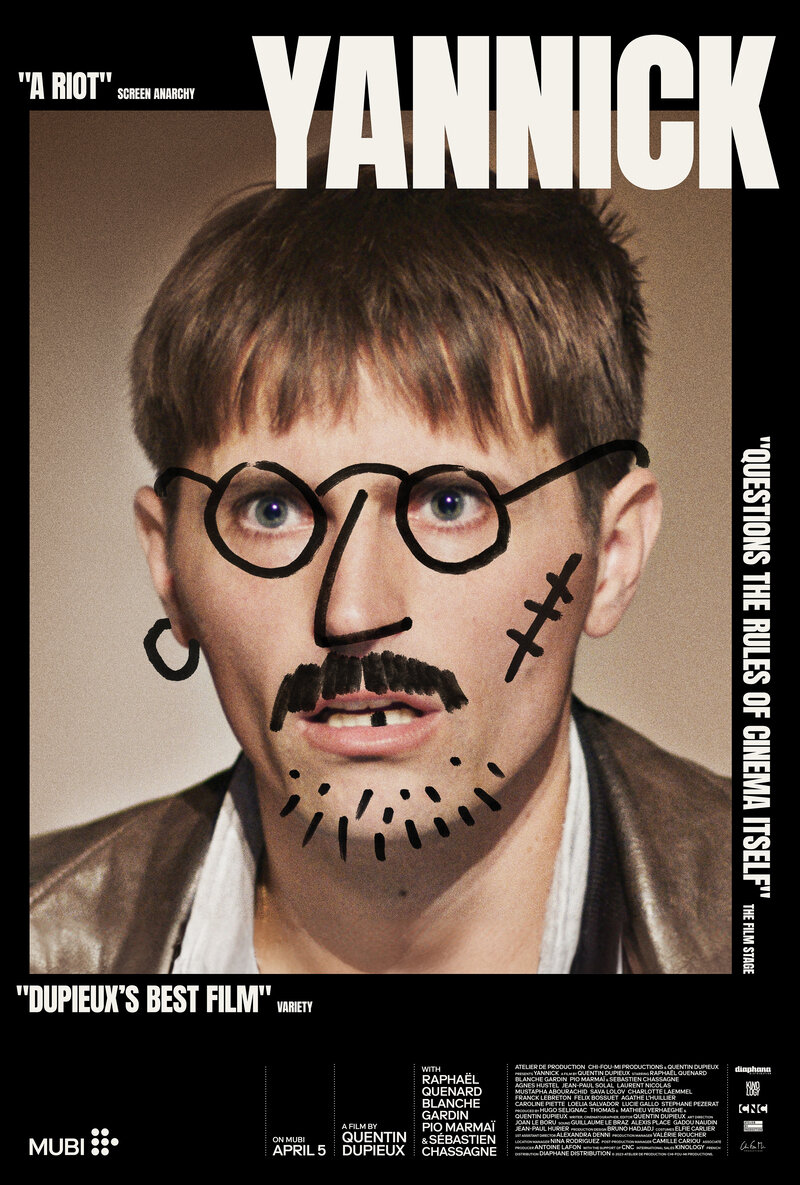

A stage production is hijacked by an audience member who claims he could

write a more entertaining play.

Review by

Eric Hillis

Directed by: Quentin Dupieux

Starring: Raphaël Quenard, Pio Marmaï, Blanche Gardin, Sébastien Chassagne, Agnès Hurstel

French writer/director Quentin Dupieux continues his prolific streak

with Yannick, which nobody was even aware of until a few weeks before its release in

French cinemas in August 2023. In the English speaking world it has skipped

cinemas to premiere on streaming service MUBI. At just over an hour in

length, Yannick probably belongs on a streaming service, lest

paying customers argue they aren't getting their money's worth.

That's exactly the complaint made by the film's titular

protagonist/antagonist, played by Raphaël Quenard. In the middle

of a Parisian performance of "Le Cocu", a mediocre comedy featuring three

actors sleepwalking through their roles to a disinterested audience, Yannick

stands up and interjects. Noting how he had to take a day off work and

commute for two hours to see the play, Yannick claims he isn't sufficiently

entertained. The actors and some audience members argue that art is

subjective, but Yannick isn't having any of it. He claims that he could

write a more entertaining play, and after being laughed at by the cast, he

pulls out a gun and demands a laptop and a printer, forcing the actors to

perform his impromptu creation to a literally captive audience.

Given its theme, it's ironic that Yannick is Dupieux's most

accessible film to date. While its premise is absurd in concept, it's easy

to imagine it occurring in real life, which isn't something you can

generally say about the crazy ideas Dupieux has conjured from his wild

imagination throughout his career. Log onto social media and you'll find a

legion of Yannicks, men (they're always men for some reason) who claim they

could do better than the latest offering from any given artist. It would be

easy to ridicule such people, especially so if you possess the wit of a

Dupieux, and I'm reminded of that time when Spurs manager Tim Sherwood

invited a heckling fan to take over his job for the remainder of the match,

which resulted in said fan being mocked by 40,000 people in the stadium and

millions more online.

It's surprising then that Dupieux is so benevolent towards Yannick. As the

film progresses, its sympathies begin to turn away from the actors, whom

Dupieux increasingly portrays as insecure and arguably as unstable as the

everyman holding them hostage, and towards Yannick, who begins to display a

level of charisma that exceeds those on the stage (greatly helped by an

oddly charming performance from rising star Quenard). Dupieux is the very

definition of a Marmite filmmaker - you're either on board with his

distinctive brand of absurdism or you're not - so it's not hard to imagine

that he's had his share of hecklers. But rather than simply use his

privileged position to belittle his detractors (like those celebs who gladly

set their millions of online followers after some random nobody on social

media), Dupieux explores the insecurity that dogs every self-aware artist.

"Wait," he seems to be asking, "Am I the asshole?"

There's a key moment that sees Yannick getting the audience on his side by

working them like Sammy Davis Jr at The Sands, which only exacerbates the

actors' insecurity. Any artist who creates something unique runs the risk of

alienating the general public, most of whom would prefer to settle for bland

familiarity (at time of writing, Godzilla X Kong is dominating

the box office). By pandering to the audience, Yannick turns them against

the actual talent in the room, the actors they originally paid to see. This

idea of making art obsolete by simply giving the public what they want has

been rapidly heightened with the rise of AI in recent times. The Yannicks of

the real world now look forward to the day when they can do without artists

and creators, when they can simply prompt a piece of software to give them

exactly what they want.

But Dupieux seems to suggest that perhaps artists and creators have played

a role in their own downfall, that maybe the work has gotten so banal that

it can be replicated by a piece of software or a deranged lunatic with a

gun. I don't see it applying to Dupieux's milieu of French arthouse cinema,

which has maintained a high standard throughout its history, but you'd have

to be deluded to argue that mainstream western entertainment is in a healthy

state. When it takes a small army of screenwriters to pen an unwatchable

superhero movie, maybe the boasts of the likes of Yannick hold some weight.

The impromptu sketch that Yannick knocks up is awful, but it's no worse than

the play he's upstaged.

With Yannick, Dupieux wrestles with the uncertain crossroads the entertainment industry

finds itself at. Is it more important to foster art or to entertain

audiences? If people prefer to eat microwaved chicken tenders than a well

prepared steak, are chefs irrelevant? Yannick gets to the

uncomfortable truth that an artist's second greatest enemy is their

audience. But Dupieux recognises that an artist's greatest enemy is their

own insecurity. Yannick tellingly ends on an ambiguous note

with the arrival of a heavily armed SWAT team. Who will be caught in the

ensuing crossfire? The artists? The audience? Both? I fear we'll receive an

answer in the near future.