Review by

Benjamin Poole

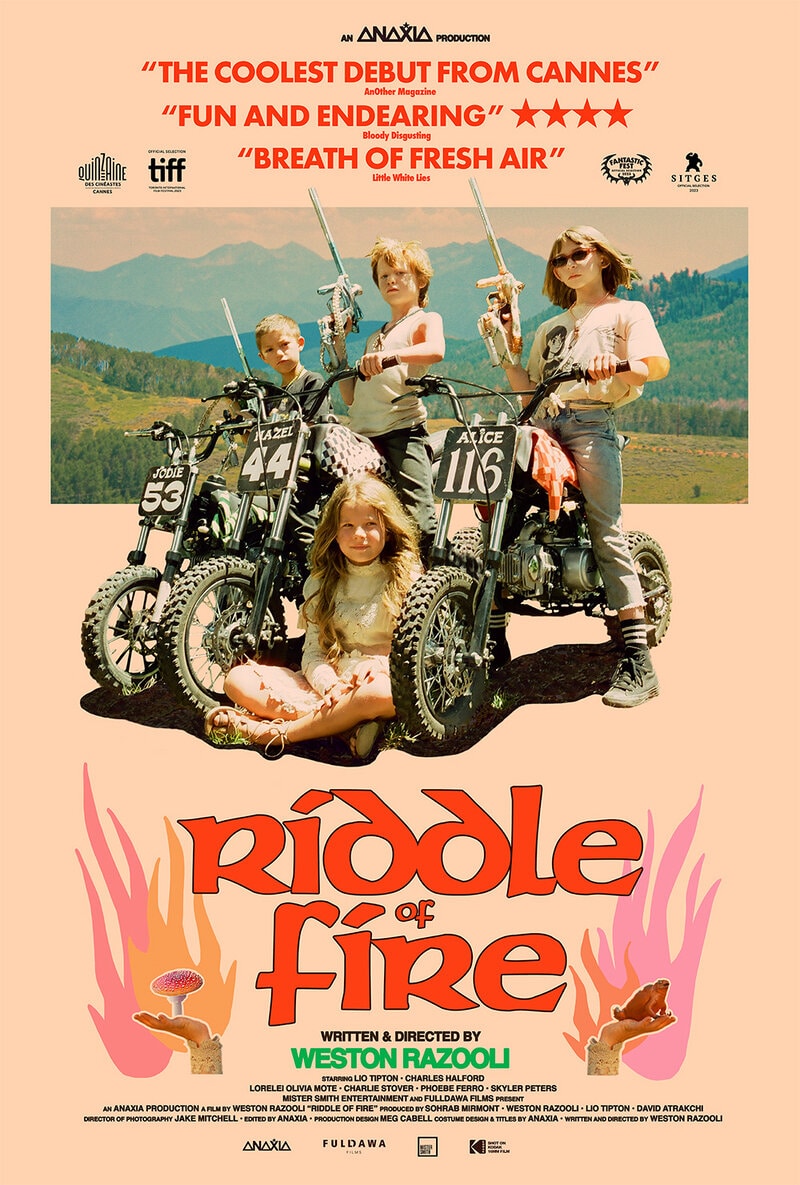

Directed by: Weston Razooli

Starring: Lio Tipton, Charles Halford, Charlie Stover, Skyler Peters, Phoebe Ferro,

Lorelei Olivia Mote

You know in Men in Black when Will Smith has that

instrument capable of wiping a specific series of events or memories

from a person’'s mind with a single extra-terrestrial flash? I've often

thought about how amazing it would be to use it to remove certain pop

culture from my brain box. Not the crap stuff, because you never

remember that anyway, but the good stuff; the good stuff which has been

parodied, memed or replicated so far beyond the original experience that

the initial impact has been besmirched. I'm thinking of the music of

ABBA divorced from its cheesy hen-night connotations and returned to

bleak pop imperialism. The epic Romantic philosophy of Mary Shelley's

'Frankenstein (the book not the Branagh). The Exorcist. It's an old man's wish, I know. And futile, too: you can't go home

again, as they say. Nostalgia is for wimps. I can no more read

'Wuthering Heights' for the first time again any more than I can ride my

kick bike to the 24/7 for a Slurpee, popping a couple a quarters into

the Pac-Man coin op before hanging out at the creek and trading baseball

cards with the rest of the eighth grade.

But the urge, the conservative need to return to the past, or at least

to duplicate those fresh and exciting formative sensations, abides. An

entire industry caters to this atavistic desire. So much so, that I'm

beginning to be gaslit into having memories of a past I never actually

experienced (I'm not entirely sure what a Slurpee is, for example).

2024's Riddle of Fire (writer/director

Weston Razooli) is such fare, tapping into a strange hauntology

with its proposed narratives of derring kid adventures, and constructing

a nostalgia so beatific and fringe that it is almost aspirational.

We are firmly within the kids-on-bikes genre here (Stranger Things, It: popularised by E.T., the auteur of which I think is to blame for this sort of wistfulness,

but that's an argument for another time) as a trio of latchkey kids

(around 10 to 12 years old, I guess) break in to a factory to steal a

video game console: when they get caught they harmlessly shoot the

startled guard with pop guns before shootin' off on their dirt

bikes.

The film goes on to introduce a MacGuffin via the kids needing to unlock

the parental protection on the family television. Their mother is

unwell, and the little smashers reason that if they can make a blueberry

pancake (do you see what I mean about construction?) she'll give in and

8bit heaven awaits. It's just so gosh darn whimsical! The

bricolage of home spun nostalgia is forceful: we'll see empty highways,

trout fishin', fairy tale magic realism; all presented within a sun

kissed frame which is as bleached out as your favourite summer painter's

cap. As it progresses, though, the narrative threatens to become Tom

Sawyer meets The Sawyers when the kids come across a drug-smoking

pseudo-culty group of dangerous poachers, with the film pushing its

sweet melancholia into a recognisable plot structure.

There is a feel of regional American folk cinema in

Riddle of Fire, a painstakingly authentic confection of not only period setting but

shrewd casting. The film also refers to exploitation texts with its sexy

gang, along with the soundtrack which invokes Fuzzbee Morse's tinkly 80s

scores. The entire film is shot using 16 mm film, too: it is clear that

Riddle of Fire is a labour of love. And if you like this

sort of thing, I imagine that it would really hit the spot. But other

than the culturally homesick, it is difficult to pinpoint who this is

for: it feels like a kiddy film you'd find on a minor channel during a

summer holiday morning, but the language and adult nature of it

restricts that potential audience. It's too long, too, with very

extended sequences where, due to the winsome amateur nature of the child

performances, you'll find yourself affecting the same supportive grimace

as when you're watching a school play in which your younger

nieces/nephews earnestly perform.

Riddle of Fire never seems cynical about its nostalgia,

quite the opposite. It has an open heart and a genuine yearning for this

era: or more accurately, the sort of movie perceived to be made during

the past. I'm sure Razooli's film will find an audience (it's too richly

made not to), but some of us, while not exactly wishing for the oblivion

of Agent K's neuralyzer during Riddle of Fire's nigh on two hour running time, may well be ruminating on how the

summer holidays really do seem to go on forever when you're younger...

Riddle of Fire is in UK/ROI VOD now.